US Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams Declaration

It is no wonder that out of the hundreds of deaths that occurred at the hands of Border Patrol agents since 1987, not a single agent has been convicted or been held accountable.

Family Members of Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca, Jorge Alfredo Solis Palma, Guillermo Arévalo Pedraza, Jesus Alfredo Yañez Reyes, José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, and Juan Pablo Pérez Santillán, Petitioners v. United States, Respondent. Case No. 15.731

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Lack of legal authority for BPCITs

- BPCITs creation

- Types of BPCITs

- Selection and training of BPCIT members

- BPCITs official purposes

- Pattern and practice of BPCITs

- First on scene

- Act as evidence collection teams for investigating agencies instead of using their professionally trained and certified teams

- Set and control the narrative

- Agents must always be the victims

- Control the investigations

- Training

- Changes since the BPCITs were made legal under CBP-OPR

- Conclusion

1) Introduction:

I served as a US Border Patrol agent from 1995 to 2001, resigning in protest because of the mass corruption and brutality I witnessed and took part in. I entered the agency with a Bachelor of Science honors degree from Auburn University in Criminal Law with an emphasis in law enforcement organization. I served as a field training agent, station intelligence agent, San Diego Sector prosecutions agent and a San Diego Sector intelligence agent. I reached the highest non-management rank of Senior Patrol Agent (SPA) and Acting Supervisory Border Patrol Agent (ASBPA). I was an award-winning agent multiple times, received accommodations, and my evaluations can be seen on my writing platform.[1] My training in investigations did not come from the Border Patrol but from my time as an intern at the Mobile County, Alabama District Attorney’s Investigative Unit and by Ed McFadden, a former Federal Bureau of Investigations special agent.

In 2020, the executive director of Alliance San Diego and the Southern Border Community Coalition, Andrea Guerrero, requested I evaluate the Anastasio Hernanadez Rojas case. The family’s attorney, Roxanna Altholz of the University of California, Berkely Immigration Clinic agreed with this request.

On May 28, 2010, Anastasio found himself in Border Patrol custody at the Chula Vista, California processing station after having crossed the border without being inspected. After an agent assaulted him for dumping water into a trashcan, he asked to see a doctor concerning pain in his ankle and was denied. Anastasio was then quickly transported to the San Ysidro port of entry for an immediate “voluntary return” to Mexico. Before being sent back to Mexico, the agents beat Anastasio ferociously. Other agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) joined in on the beating, kicking, punching and tasing him at least four times. Anastasio died days later.

What Ms. Guerrero and Ms. Altholz did not expect was that the Anastasio case documented the acts of the Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams. Unknown to those outside the agency, these teams worked day and night to prevent every single agent who killed, beat, assaulted, ran over, or injured people in use of force incidents from being held accountable. Since 1987, not a single agent has ever been held accountable criminally for the killing of a migrant, resident or US citizen. That is because these teams were and still are the largest coverup unit ever known to exist. They were secret even within the agency.

In researching the Anastasio case and continuing that research on my own, I found what I knew as an agent in the mid 1990s was still true in 2021: the teams still existed, they had grown into multiple teams per sector, trained hundreds of agents in their pattern and practice of obstructing justice, expanded past the southern border sectors and were being used by local, state and federal agencies who were legally required to investigate Border Patrol use of force incidents as official evidence collection teams in most incidents. As when I was an agent, the knowledge of these teams we often referred to as “coverup teams” was on a need-to-know basis. Only agents who had been involved or responded to use of force incidents knew about these teams. Those agents who could not be trusted to keep the secret or had been mostly administrative agents and did not work the field much, often went their entire careers not knowing about the teams.

My personal experience with the teams and my work on the Anastasio case was documented with the publishing of my memoir in 2022, “Against the Wall: My journey from Border Patrol agent to immigrant rights activist.”

This declaration will show that the US Border Patrol not only violated Anastasio’s right to life and liberty, but that this behavior is systemic and institutionalized within the agency. Policies and procedures have been developed specifically within the Border Patrol to ensure that agents and the agency itself are never held to account for their human rights violations. The Border Patrol is well versed in creating what appears as confusion and incompetence to the public and the press but is instead intentionally designed failures. Evidence is intentionally lost, witnesses are deported or disappear, investigative authorities are not called in a timely matter so that the coverup teams can get the narratives established. What seems like general incompetence to outsiders is intentional obstruction of justice that was developed and has been used in the agency for decades. The result of this criminal behavior are flagrant abuses of civil rights and human rights that result in failed investigations, partial investigations that are eventually dropped and sometimes no investigations at all.

Anastasio was not the first to die at the hands of these agents, nor was he the last. However, his case offered what many others did not: a wealth of documented evidence and information about a rarely ever discussed and little-known department within the Border Patrol called the Critical Incident Team (BPCIT). The acronym is pronounced “sit.” Hundreds have lost their lives at the hands of the Border Patrol and CBP. No matter who investigated the incidents, every case touched by the BPCITs was contaminated. Many families have no idea what happened to their loved ones or why.[2]Of all these deaths, only one agent has been tried in a court of law. That agent, Lonnie Schwartz was later acquitted in the death of Jose Antonio Elena-Rodriguez.[3] The Jose Antonio case also provided a great deal of insight into how the teams work and what they believe they are allowed to do as an evidence collection team. Like many other deaths caused by agents, the evidence in both the Anastasio and Jose Antonio cases was overwhelmingly that deadly force was not justified according to the Border Patrol’s own use of force policies.

In October of 2021, Alliance San Diego and the Southern Border Communities Coalition sent their complaint about the secret and illegal teams to Congress.[4] In January 2022, Congressional members of several congressional committees demanded investigations into the coverup teams though no investigations have been held as of the writing of this declaration.[5] On May 3, 2022, then Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Chris Magnus ordered the elimination of the BPCITs to occur with the new federal fiscal year in October of 2022.[6] However, in October of 2022, the Biden Administration allowed Border Patrol Critical Incident Team agents to resign from the Border Patrol and then rehired them under Custom and Border Protection’s Office of Professional Responsibility (CBP-OPR) which does have the legal authority to investigate Border Patrol use of force incidents.

This meant that the same agents responsible for thirty-five years of secret coverups and obstruction of justice were legalized under CBP-OPR investigations that was led by former Border Patrol agent Daniel Altman until April 30, 2025, and is staffed with mostly ex-Border Patrol agents. A CBP memorandum also stated that the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division would investigate the coverup teams prior to them being legalized.[7] This is the same Civil Rights Division that used the illegal BPCITs’ investigations to deny cases for thirty-five years.

Currently, the former illegal and secret teams have been rolled into CBP-OPR and are still being used as evidence collection teams for current cases. It is not known if these agents ever received professional evidence collection or forensics training after they transitioned to CBP. No agent has ever been held accountable for these teams or their actions.

It is implausible, statistically impossible even, that every single shooting or beating that occurs at the hands of Border Patrol agents could be considered what the agency terms as a “good shoot” or a “justified use of force.” Likewise, it is doubtful that every single court in the United States that has heard one of these cases is somehow in league with the agency. While each case is different, there is one constant that remains in all of them: the illegal and secret CIT units responded.

2) Lack of legal authority for BPCITs:

For a US federal law enforcement agency to create a new authority, they must first have that authority given to them by the US Congress. There is no legal authority granted by Congress for Border Patrol to act as evidence collection teams or to investigate their own use of force incidents. In fact, the agency is expressly forbidden to do such investigations by law.

Legal authority for Border Patrol agents can be found under 6 USC 211.[8] Although this authority allows agents to enforce federal immigration, customs and narcotics laws and to conduct preliminary investigations in these areas, these investigations are limited. The agency’s authorities are listed under the Office of Professional Management 1896 series[9]designation instead of the 1811 series[10] of authorities that agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) and other investigative agencies hold. This is what limits extensive investigations by Border Patrol agents.

Additionally, Congress limited the agency’s authorities through 8 USC 1357(a)(5)(B).[11]The law further states that Border Patrol arrest powers outside of their authorities are legal only if agents are performing their immigration duties at the time. These limited powers legally prevent Border Patrol from investigating their own use of force incidents.

This is backed up by testimony from former Border Patrol Chief Michael Fisher in the federal court case of Maria del Socorro Quintero Perez et al v. Dorian Diaz & US(#13cv1417-WQH-BGS):

“In order to avoid any conflicts of interest, CBP [the chief uses CBP though he is speaking only about Border Patrol as CBP does have investigative authorities] was not allowed to investigate incidents of lethal force relating to its own agents while I was serving as Chief [of Border Patrol]. I did not receive or review the investigations by the Office of Inspector General, the FBI, or any other outside law enforcement agencies who investigated instances of lethal force because I did not have investigative authority within CBP [Border Patrol]. For any incident involving use of force, [Border Patrol] would compile a document entitled Critical Incident Investigative Team Report [San Diego Sector’s BPCIT was called a Critical Incident Investigative Team] but those reports contained no findings made by CBP [Border Patrol] or actions taken by the CIIT team-...”[12]

Federal agencies with authority to investigate Border Patrol include the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General (DHS-OIG), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), or Customs and Border Protection’s Office of Professional Responsibility (CBP-OPR). Local and state law enforcement agencies may also investigate use of force incidents by Border Patrol when they are committed within their jurisdictions.

3) BPCITs creation:

In 1984, the Border Crime Prevention Unit (BCPU) was created by San Diego Sector Chief Alan Eliason to address crime and violence experienced by migrants in the Imperial Beach border area. Border Patrol agents were assigned to the unit worked with members of the San Diego Police Department to arrest bandits harming migrants in the canyons. The BCPU only lasted from 1984 to 1988 because of the level of violence experienced by agents was not only extreme, but the team itself had shot not only bandits, but migrants as well.[13] It was not uncommon for the team to encounter small groups of armed bandits working the canyons just north of the border together. In 1986, the BCPU reported that they were confronted several times with armed bandits who intentionally set up ambushes for the agents. In the four years that the unit operated, “members of the BCPU were involved in a total of thirty-five shooting incidents that resulted in three members being shot and wounded themselves.”[14]

It is my hypothesis that this led to the development of the Critical Incident Teams. With thirty-five shootings in just four years, San Diego Sector Border Patrol management was facing dozens of possible criminal and civil cases being filed against agents and the agency. Not only were his agents’ careers at stake, but the reputation of the Border Patrol was being tarnished as well. When border rights groups began protesting the violence and shootings committed by the task force unit and the pressure was on to do something from the public, San Diego Sector management chose to create a secret and illegal coverup team instead of addressing the actions of their agents.

In 1987, San Diego Sector Border Patrol Chief Dale Cozart created a new sector unit within the existing Sector Intelligence Unit called the Critical Incident Investigative Team or CIIT, pronounced “sit” among San Diego agents. What was described by the Chief as just another intelligence duty later became the largest and most secret coverup unit ever discovered among law enforcement agencies in the US.

Each sector’s Critical Incident Team was individually designed. This is why they have different names. Known names of these teams include Critical Investigative Incident Team (CIIT), Sector Evidence Team (SET), Critical Incident Team (CIT), Evidence Collection Team (ECT), Critical Incident Response Team (CIRT) and Cross Border Investigative Unit (CBIU). Additionally, when these units were unavailable, chiefs of sectors used the agents assigned to the Sector Intelligence Units (SIU) and Sector Smuggling Interdiction Groups (SIG) to respond to use of force scenes and provide the same coverup schemes as they had also been trained by the BPCITs.

For consistency, this report will use the term Critical Incident Team or BPCIT for all Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams to not confuse readers.

4) Selection of training of BPCIT members:

BPCIT agents were personally selected by the chief of each sector. In general, each sector team had one or more Critical Incident Teams consisting of a handful of temporarily detailed agents, a lead or senior agent and a supervisory agent. Above the supervisory agent, command consisted of a selected assistant chief, deputy chief and the chief of the sector. The agency told the investigative agencies that BPCIT agents were only to be a liaison between the investigating agencies and the Border Patrol, but this was not true.

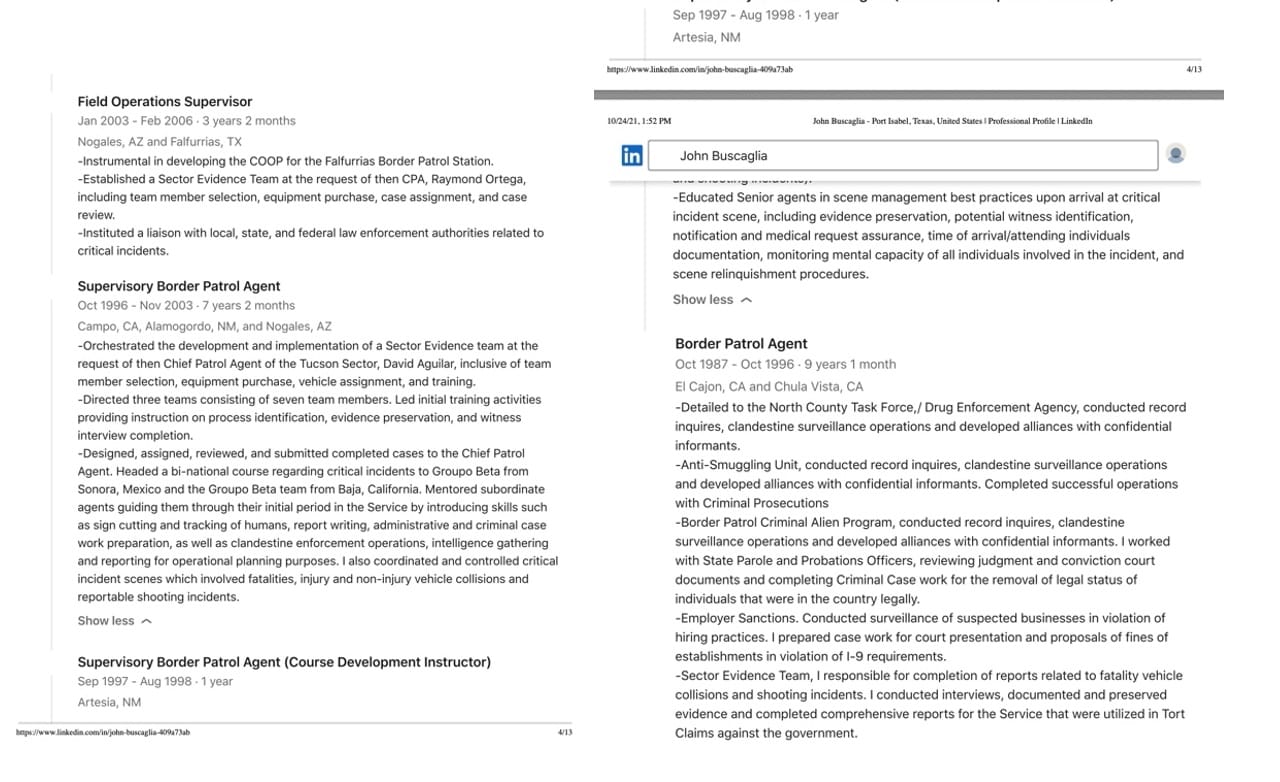

My research conducted into these teams has revealed that few agents contributed more to the development of these illegal teams than former Assistant Chief Patrol Agent John Buscaglia. In October of 2021, I discovered his public LinkedIn account which documented how the teams spread from San Diego to other sectors. As the following screenshots show, Buscaglia was instrumental in creating new BPCITs for the chiefs of other sectors and was responsible for creating the secret academy training used to teach agents evidence identification, collection and analysis. It is not known if any of these courses were certified by professional forensic organizations as is standard for local, state and federal agencies with these authorities.

Former Assistant Chief John Buscaglia developed and created illegal and secret Critical Incident Teams in many sectors.

5) BPCIT official Purposes:

There is no official statement from the US Border Patrol nor Customs and Border Protection on what the purpose or functions of the BPCITs were because they are considered by the agency to have never officially existed. I have found few mentions of BPCITs in public government documents. Prior to 2014, the Border Patrol’s Use of Force Handbook that I was trained with was considered “law enforcement sensitive” and was therefore secret. In the 2010s, as killings by agents increased, the agency was forced by the federal government to submit their secret handbook to The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for evaluation by law enforcement professionals and experts. The 2013 PERF Report noted that the 2010 Use of Force Handbook mentioned the BPCITs but did not explain what they were.[15]

Page 14 of the PERF report indicated that the original Use of Force Policy Handbookstated:

“Chapter 5: Use of Force Reporting Requirements

Recommendation: In Section A, 4, c reference is made to a Critical Incident Team (CIT) that may initiate a parallel investigation into an incident. There is no other definition or description of a CIT. Such information should be added to the Handbook.”[16]

Once the revised 2014 Use of Force Policy Handbook was released to the public for the very first time, the reference to BPCITs was removed.[17] Instead of following the recommendations of the PERF report in 2013 to describe what the BPCITs were and what they did, CBP and Border Patrol decided to eliminate any mention of it and the teams remained secret. Still, policy for agents remained as the formerly secret handbook had ordered, to notify the BPCITs first before any outside investigations occurred.

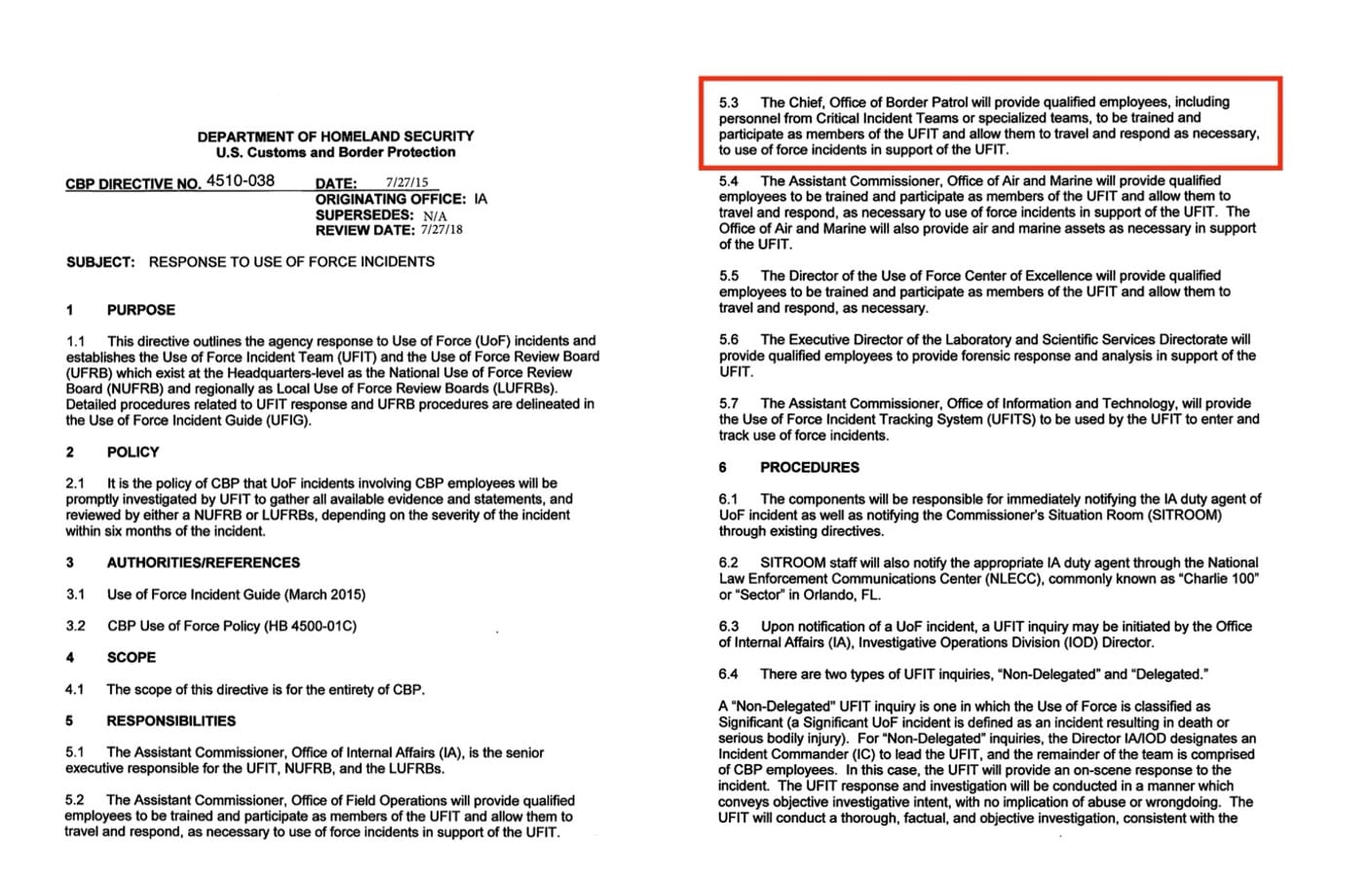

Additionally, Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Gil Kerlikowski announced they would release a new directive on how Border Patrol and CBP should handle critical incidents in 2014. CBP and Border Patrol designed a system of additional oversight to convince Congress, law enforcement and the public that all Border Patrol use of force incidents were reviewed several times by experts within law enforcement and that this group, known as the new National Use of Force Review Board (NUFRB), were independent of the CBP and Border Patrol. This also included groups called Use of Force Teams around the country known internally as UFITs.[18]

The problem with this response was that by the time the directive came out in 2015, it was not released to the public. The internal directive made clear from the beginning that CBP and Border Patrol did not create an independent oversight group in the NFURB. Unknown to Congress, media, oversight agencies and the public was that the agencies not only continued to use the illegal and secret BPCITs to identify and collect evidence, but they also used them as investigators and members of the UFIT and NUFRB teams.

The US Border Patrol and CBP went out of their way to create an entirely new system to assure Congress and the public that they would have independent review of their use of force cases, and it worked. The secret and illegal BPCITs remained and took on more authorities that they never had the legal right to possess. Instead of admitting they were using these secret teams, they kept them hidden and BPCITs continued to be the first to respond, choose the evidence they wanted and obstruct where they could. It was never a problem of training or guidelines like they suggested to the public and Congress. It was always about hiding the BPCITs.

There has never been an official explanation given to the public or to Congress as to the existence and purpose of these secret teams, yet this unit is present at every single shooting, beating, rape, death, rocking, car accident, etc. It is also clear that with every “critical incident,” these teams were sent out to work either alone or alongside other investigative agencies that were investigating the use of force violations of Border Patrol agents. But publicly and in court, former Border Patrol Chief Fisher admitted in 2017 that teams were not legally allowed to do this work.[19] According to statements made by Chief Fisher, CIT reports were merely “just duplicated copies” for “internal use” and were not even used in disciplinary matters.

Chief Fisher was not truthful when he testified about the purpose of the teams. In the Anastasio killing, Border Patrol Union attorneys used the team’s report to create doubt in jurors and court’s mind when the evidence collected by the team was contaminated. In the Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez killing in October of 2012 in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, Union attorneys used the poorly trained CIT unit’s to create enough doubt that two juries could not reach a decision.[20] Sean Chapman, long-time Border Patrol Union attorney stated, “Flaws in the investigation on both sides of the border impact the integrity and the reliability of the evidence.”[21]

Chief Fisher was under scrutiny in 2017 from Congress for increases in beatings, tasings, shootings and cross-border shootings by his Border Patrol agents that never seemed to hold anyone accountable except for the victims. Each time these incidents happened, evidence went missing or was collected poorly, witnesses were intimidated or deported and not once was an agent held accountable for their actions.

Since the agency quietly deleted the order to call the illegal and secret Critical Incident Teams from the new public and no longer “law enforcement sensitive” 2014 Use of Force Handbook, most believed the articles written by numerous border reporters that each case was being handled by independent agencies with the legal authority to investigate.

6) Pattern and Practices of BPCITs:

a) First on the scene:

When Anastasio Hernandez Rojas was killed in May of 2010 from being beaten and tased, the first to respond was the San Diego Sector BPCIT. The unit was immediately notified by the San Diego Sector Dispatch once an ambulance was requested. This was recorded on dispatch records and was in accordance with Border Patrol official policy of the time as shown in the 2010 Use of Force Handbook. In violation of policy, San Diego Border Patrol management failed to call all other agencies with authority: San Diego Police Department, Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General and the Federal Bureau of Investigations. (Customs and Border Protection’s Internal Affairs did not start until 2012 and ended in 2014. Customs and Border Protection’s Office of Professional Responsibility did not exist until 2016.)

Anastasio’s case is just one of example of hundreds showing how the Border Patrol used the CITs to obstruct justice and spy on investigative agencies to control the investigations into its agents and their crimes. BPCIT agents had control of the crime scene for at least fifteen hours after the incident, before the San Diego Police Department was notified. Even then, it was the media who told them of the beating and not the Border Patrol.

When the BPCITs were unavailable, sector management would send other units like the Sector Intelligence Units (SIUs) or Smuggling Interdiction Groups (SIGs). One of the practices of the BPCITs was to take on many agents for training so that when critical incidents happened, there was always an agent available who had some training in the patterns and practices of the coverup teams.

When Valeria Tachiquin Alvarado, a US citizen and mother was shot and killed by Border Patrol agent Justin Tackett on September 28, 2012, the San Diego BPCIT was unavailable. Agent Tackett was not in uniform when he knocked on an apartment door in Chula Vista, CA. Valeria answered the door and when she tried to leave the scene, she was followed by Tackett and other plain clothed agents to her car. Agent Tackett blocked her car with his body and as she tried to go around him, he claimed her car brushed his leg. Agent Tackett drew his weapon as his partner shattered Tachiquin’s driver’s window. Tachiquin continued to drive away when Agent Tackett claimed he was forced onto the hood of her car. He shot her multiple times killing her.[22]

Chief Rodney Scott (current CBP Commissioner) ordered the Sector Intelligence Unit to the scene and obstructed Chula Vista Police from accessing them. Even though the BPCIT was not there, they caught up with the investigation where the SIU left off. This information was obtained through my contacts with members of the San Diego CIT.

On February 19, 2022, Carmello Cruz Marcos was shot and killed by Border Patrol Agent Kendrick Bybee Staheli in a remote canyon in the Tucson Sector. The Tucson Sector is notorious for violence against migrants and maintained multiple BPCITs. Cochise County Sheriff’s Office had the authority to investigate, and while called by the Border Patrol, the BPCIT refused to assist investigators get to the scene until the next day. The Tucson BPCIT had control of the scene sending in BORTAC agents who did not have any training in securing crime scenes.[23] This was one of the last cases the BPCIT worked on before being moved to Customs and Border Protection’s Office of Responsibility.

As the BPCITs were developed in the 1990s by Agent John Buscaglia, they replaced the professional evidence teams used by investigators at the local, state and even federal level.

On October 10, 2012, fifteen-year-old Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez was shot ten times in his back and the back of his head as he walked down the street to visit his brother in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Border Patrol Agent Lonnie Swartz claimed rocks were being thrown by Jose Antonio, stuck his gun in between the border fence bollards and fired, reloaded and fired more while standing in the US. BPCIT agents were notified first and then notified FBI Special Agent Michelle Terwilliger. Terwilliger testified that she then gave the BPCIT agents permission to go ahead and identify and mark evidence. Her sworn courtroom testimony was that the FBI always used the BPCITs as evidence collection teams when the Border Patrol was involved and not the FBI’s well-known professional teams.

While the shooting occurred at 11:27pm local time, BPCITs did not show up to the scene until 1:00am on October 11th. This left the scene in the hands of the shooter and other agents involved in the incident for over ninety minutes.[24]

While agents on the scene waited for the BPCIT unit to show, senior Border Patrol Agent Roy Pierce took it upon himself to wrap the scene on the US side with yellow caution tape, identified and marked bullet casings, and took pictures of the scene where Jose Antonio’s body laid on the Mexican side. In courtroom testimony, Agent Pierce stated that he had been trained in evidence preservation. Although he did not specifically mention the CIT, this is the only unit that trained agents in such tactics. While Agent Pierce’s actions that evening were not illegal, and although he bragged on the stand about having evidence preservation training and skills, he still failed to preserve the scene when video later revealed that Agent Pierce, as well as several other agents, drove through the crime scene. Agents were also recorded running through the area where shell casings and the rocks alleged to have been thrown were located.[25]

BPCIT agent Gerardo Carranza admitted on the stand that when he arrived on the scene ninety minutes after the incident, agents involved in the shooting had gathered evidence such as rocks and placed them in a pile.[26] When FBI Special Agent Terwilliger arrived, she testified that she personally identified and bagged all the evidence, but was forced on the stand to finally admit this was not true by Border Patrol Union attorneys. The BPCIT did the 3D scan of the scene using their own scanner and had custody of the some of the evidence.[27]

About six hours after US citizen Steven Keith pulled up to the Interstate 8 Checkpoint in Pine Valley, California, he was dead inside the Campo, California Border Patrol Station. The San Diego Sector BPCIT and the San Diego Sheriff’s Office were called. In an interview I conducted with Steven’s sister, Jan explained to me that it was her understanding that Border Patrol Critical Incident Team Agent Tracey Wong had done the homicide investigation. When I told her that was not possible, she stated she had never received any official response from any agency on who did the investigation. Thirteen years later, I obtained the Sheriff’s report that stated they did respond but that BPCIT Agent Wong had conducted the official homicide investigation.[28]

This means that Steven, an American citizen never received a legal investigation into his in-custody death because the San Deigo Sheriff’s office just let the Border Patrol handle it. No criminal charges were ever filed, and the family could not file a civil suit because the BPCIT refused to give them any information.

c) Set and control the narrative:

Like all other BPCIT use of force cases I have studied, the agent using force must justify their actions by showing that they perceived a threat to either their life or the lives of others. These carefully constructed narratives begin in Border Patrol/CBP Serious Incident Reports and Use of Force Reports. Both are used to convey facts as well as intentional misinformation and often outright lies. Information that support the agencies’ narrative that the use of force was justified were/are included in these reports. Most often, Border Patrol managers simply omit the important facts that can tell a different story.

Both reports are sent to Washington D.C. Border Patrol and CBP headquarters with updates constantly being made months, sometimes years after the incident. In the Jose Antonio killing, the Serious Incident Report for this case falsely stated that Nogales Police Department Officer John Zuniga’s K-9 was hit by a rock.[29] This was later proven in court and by the handler’s own testimony to be not true.[30] The report also assumed that the person killed, Jose Antonio, threw rocks without any evidence other than the word of Agent Swartz who was not present when the incident started.

Border Patrol then leaked this false information to the press through their spokespersons and repeated these statements so often that the media routinely reported that Jose Antonio was throwing rocks although at least three witnesses who were never interviewed by the BPCIT stated he was simply walking and had nothing to do with those who were throwing rocks. The first story printed by the media on October 12th was by the Arizona Daily Star and entitled, “Nogales crowd pelted officers with rocks after drug drop, agency says.”[31] Reporter Tim Steller wrote this because this is what Border Patrol and CBP told him, but video proved many years later in court that none of the agents “ran” or even considered themselves to be in danger.[32]

In this first article written about the case, the Border Patrol controlled the narrative. While first stating the obligatory phrase that they did not want to comment on the case for fear of influencing it, the agency spokesperson went on to say that the shooting was the result of agents being attacked by rocks, and that the agents reportedly ordered those in Mexico to stop throwing rocks. When their orders were ignored, an agent shot into Mexico. The spokesperson then stated that the investigation was being done by independent investigators of the FBI and the Sonora, Mexico State Police. There was no mention that the illegal BPCIT unit handled the evidence identification and collection for the FBI.

This framing of investigations as impartial and independent is most important and is seen in nearly all cases involving the Border Patrol. On the following day and every news article thereafter, Border Patrol officials repeated that they did not want to talk about the case for fear of influencing the investigation and potential jurors. Yet each time, they turned right around and talked openly about the case to the media spreading false information about the victim. The second article in the Arizona Daily Star quoted agents as saying Jose Antonio was “suspected” of throwing rocks.

In the Anastasio killing, San Diego Sector Chief Rodney Scott signed an administrative immigration subpoena and had BPCIT serve it on the medical examiner to get a copy of the report before the San Diego Police Department’s homicide detectives could get ahold of it. When they asked for a copy, Chief Scott refused citing irrelevant HIPAA laws. They used this report to leak to the press that drugs were found in Anastasio’s blood but later could not prove the blood was his in the civil trial. The narrative that Anastasio was a crazed drug addict was established.[33]

The setting of the narrative with the media by the Border Patrol and its union while simultaneously claiming they do not want to influence or prejudice cases is consistently seen in nearly every single case across various CIT teams in differing sectors and is pattern and practice within the agency.

d) Agents must always be the victims:

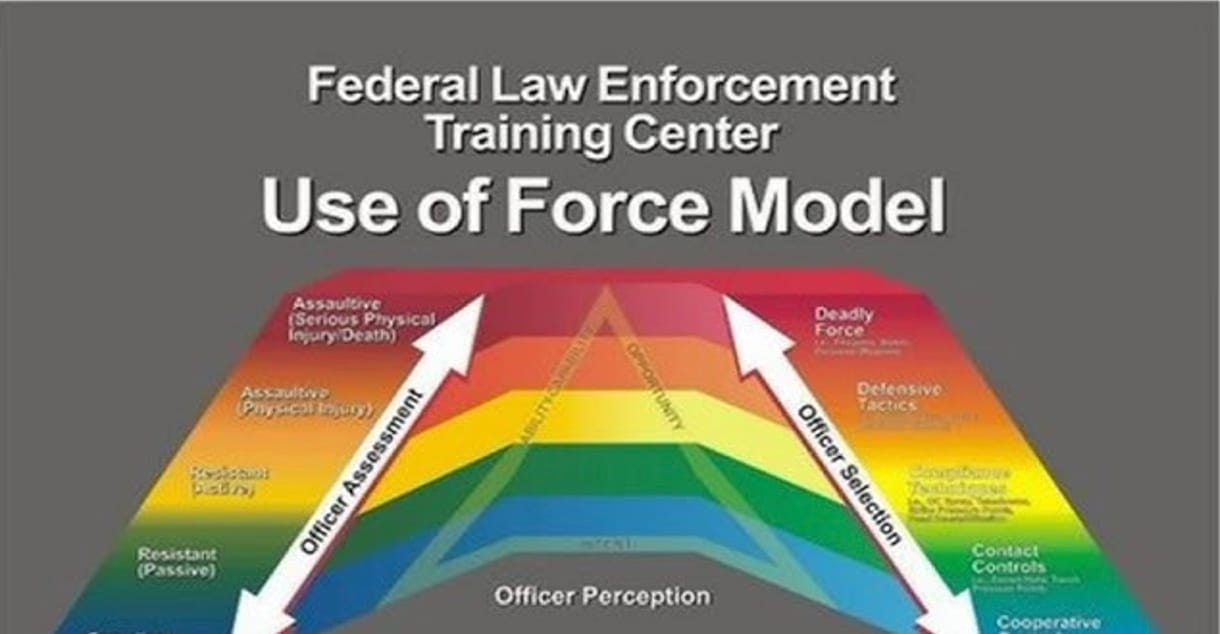

Once the narrative is set, Border Patrol unleashes their press information officers and the Border Patrol Union to hit the media hard with their version which almost always insists that the agents are the victims. This is because US law requires agents use an amount of force that is equal to the amount of resistance. This is seen by their use of force continuum models that are taught at the Border Patrol academies held in Federal law Enforcement Training Centers.

When Anastasio was beaten and tased with his hands behind his back, the narrative Border Patrol went with according to former Commissioner of Internal Affairs of CBP at the time James Tomsheck, was that he was not handcuffed behind his back. This is because using lethal force on a person while their hands are handcuffed behind their back violates the use of force continuum.[34] It did matter to the agency that this was not true because they believed at the time that they had confiscated or erased all witness videos. Years after the incident, a video surfaced that showed Anastasio lying in the fetal position with his hands handcuffed behind his back as agents circled around him and beat and tased him to death.[35]

When Valeria was shot by Border Patrol Agent Tackett, former Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott ran down to the scene and told local media that she had tried to run over the agent making him fear for his life even though the scene had yet to be evaluated.[36]

When Carmello was shot and killed by Border Patrol in Arizona, witnesses stated that they heard agents involved saying they would just say he was going to throw a rock at him to create the need to use lethal force.[37]

When Jose Antonio was walking down the street in Nogales, Sonora, Agent Swartz claimed a Nogales Police Department K9 was injured by rocks thrown by Jose Antonio even though he did not witness the events and witnesses stated that he had not thrown rocks.[38] He then claimed he heard agents say this over the radio, but no proof was ever given in court and the K9 handler stated his dog was never hit by a rock and that he never stated that he was.[39]

The list of cases demonstrating this practice is extensive. I have seen this in nearly every BPCIT case I have studied. It is the agent who always “fears for their life,” a statement that I and all agents were/are trained to say when they physically harm someone.

e) Control the investigations:

As shown, investigations into Border Patrol use of force incidents are highly controlled by the BPCITs. By being the first to the scene and working as evidence identification and collection teams for legitimate and legal investigative agencies, they got to decide what was marked as evidence and what was not. In the Jose Antonio killing, BPCIT was found to have let the agents involved in the shooting decide what rocks were evidence. Bullet casings and rocks underneath cars were missed.

Gary A. Rini, expert witness in forensics analysis testified in court that the BPCITs,“did a less than thorough job in collecting rocks. Since this was the alleged weapon that was used, you want to be able to collect rocks not just from a specific area, but from the surrounding area as well.” He stated that they should have done DNA testing on the rocks, that they failed to interview the camera operators until later. He believed eyewitness evidence was lost and that they lost video of the incident. They failed to conduct a gunshot residue test on the fence, which he stated should have been done to identify where Border Patrol Agent Swartz was standing when he fired. He mentioned the video of Border Patrol trucks and agents driving and walking through the scene that ran over and displaced evidence. On BPCIT agent Carranza using the Total Station 3D Laser, he stated: “That the individual who responded to collect the -- or to conduct the Total Station system, basically to document the system electronically, I think the term was, screwed it up. Those may be my words. But anyway, it didn’t work out, screwed it up.”[40]

In the Anastasio case, BPCIT left evidence behind at the scene, failed to collect all the evidence, failed to collect the victim’s clothing,[41] gave the wrong video to the San Diego Homicide Team and then stalled for weeks until they finally claimed the video had been erased.[42] CBP agents admitted to seizing witnesses’ phones and erasing videos and images of the beating.[43] BPCIT allowed the agents involved to speak to each other and go home to shower and change before evidence could be collected. The vehicle used to take Anastasio to the port of entry was never analyzed by any evidence team.[44]

In Carmello’s killing in 2022, BPCIT placed all witnesses to the shooting in one vehicle and then placed them in one holding cell. This was a common tactic used by the teams when I was an agent. If these cases end up in court, Border Patrol Union attorneys could then claim the testimony of the witnesses was contaminated because they could have been talking with each other about the case. This was noted by the Cochise County Sheriff’s investigating the incident as reasons of why their testimonies should not be considered.[45]

When victims’ bodies fell/fall in Mexico, the BPCITs still controlled the narratives. Former Assistant Chief John Buscaglia stated in his LinkedIn Profile that from 1996 tom 2003, he “Headed a bi-national course regarding critical incidents to Groupo Beta from Sonora, Mexico and the Groupo Beta team from Baja, California. It did not matter that Mexican police were conducting part of the investigations because the agency had assured that their investigators were trained just as their BPCITs wanted them to be trained.

Case after case from 1987 to 2022 that was covered in the media repeated the claims of various Border Patrol spokespersons that each one was being investigated by independent, professional and legal investigative agencies. Families and often their attorneys never knew that it was Border Patrol agents, the coworkers of those using force who did not have the legal authority to conduct such investigations, that were deciding what was evidence, that often gathered the evidence so poorly that they contaminated it, that they often intentionally destroyed evidence and were manipulating the investigations to control the narrative.

8) Training:

It is difficult to know how BPCIT agents were trained because the agency refuses to release this information. The Jose Antonio killing provided the most information how this was conducted during that time.

According to BPCIT Agent Gerardo Carranza, he had been with the unit six months when he responded to the incident that night.[46] When asked what the job of CITs was, he testified that the units had extensive investigative reach:

“The Critical Incident Team, basically we went out and did a third-party investigation for the Border Patrol. We investigated and collected forensic data in regards (sic) to shootings, uses of force incidents, collisions, things like that. Anything that the Border Patrol deemed to be critical and there might be some media attention, or somebody was hurt, injured or killed.”[47]

Carranza stated that he used the BPCIT 3D scanner from Total Station to map the scene on the US side.[48] He stated that his CITSupervisory, Katie Seimer used the Total Station prism pole to align evidence markers with the laser.[49] Days after the incident, they recreated the scene using Total Station at their CIT offices which contradicted FBI Special Agent Terwilliger’s testimony that she collected and analyzed all the evidence herself.[50] After recreating the scene, he realized there were errors, and that they “overshot” two of the shell casings and the data was missing.[51]To fix the error, he stated they used photographs to then place the two missing shell casings into the 3D diagram.[52] Carranza stated that they did not shoot the scene in 3D but in 2D that night, causing the evidence to appear as if it were floating in the diagram produced for court.[53] He testified that training for the 3D scanner was a class taught by another BPCIT member who gave them a verbal pass or fail. There was no official, approved training given to the BPCIT agents other than “on the job training.”[54]

It is not currently understood where BPCIT’s budgets came from or how purchasing was conducted for a unit that was secret and had no authority to exist. It is likely that then 1987 San Diego Sector Chief Cozart paid for the first BPCIT by placing them under sector intelligence. Procurement prior to the creation of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is even more difficult to ascertain as the databases are not available.

After CBP was established and Border Patrol was placed under CBP, BPCITs’ procurements came from CBP’s Laboratory Science Services (LSS). Purchases were hidden within LSS contracts and in Department of Homeland Security purchasing. It only once you open the massive files that you can find some of the federal procurement logs for BPCITs. This where you can find purchases for 3D scanners, latent fingerprint fuming chambers, crash reconstruction and other forensic and evidence training and tools. Although it is good that the teams finally received official training, they still did not have the legal authority to conduct such investigations.

Procurement logs show CBP hid purchases for illegal CITs within CBP-LSS.

The fact that the US Border Patrol used illegal and secret Critical Incident Teams to act as evidence identification and collection teams in their own use of force cases denied victims their right to a fair investigation and equal protection under the law. Victims and their families were denied the right to an investigation and access to justice every time these illegal teams showed up on a crimes scene, every time they sat in on investigators’ interviews of witnesses and victims to spy on the actual investigations, every time they failed to gather evidence, every time they failed to collect it properly, every time they failed to store it properly, every time they analyzed it, every time they testified in court and were accepted as evidence and forensic experts.

9) Changes since the BPCITs were made legal under CBP-OPR?

The biggest change since the BPCITs were moved into Customs and Border Protection’s Office of Professional Responsibility (CBP-OPR) is that they have become more secret. After this transition, Border Patrol agents on the Tohono O’odham Nation in Arizona shot and killed Raymond Mattia on his own land after he called for help with migrants on his property.[55]

When the Tucson BPCIT showed up in their new CBP shirts, not much had changed. They said nothing to the family or to their attorneys about why he was shot. CBP later claimed Raymond threw an “object at them.”[56] This was later discovered to be a machete that he was asked to toss on the ground. The video showed he did as he was ordered. It was only after he was ordered by agents to take his hands out of his pockets, that three of the ten agents fired their guns severely injuring Raymond. He gasped for air and rolled around before dying. He did not have a weapon, but instead the cell phone he had used to call for help.[57]

Immediately after the shooting, agents are seen running around in a chaotic fashion trying to find a gun that Mattia never had. In the process, just as they did in the Jose Antonio shooting, they likely destroyed much of the evidence. CBP-OPR later released the video, but it was highly edited and only contained the footage from the three agents who shot and not all the agents present that night. Days later, the Border Patrol Union’s vice-president Art del Cueto went on the Union’s podcast and announced that he had seen the evidence and that the shooting was within the use of force policy. He also stated that Raymond had a prior criminal record for sexual abuse to smear the dead man.[58] CBP cleared all involved.

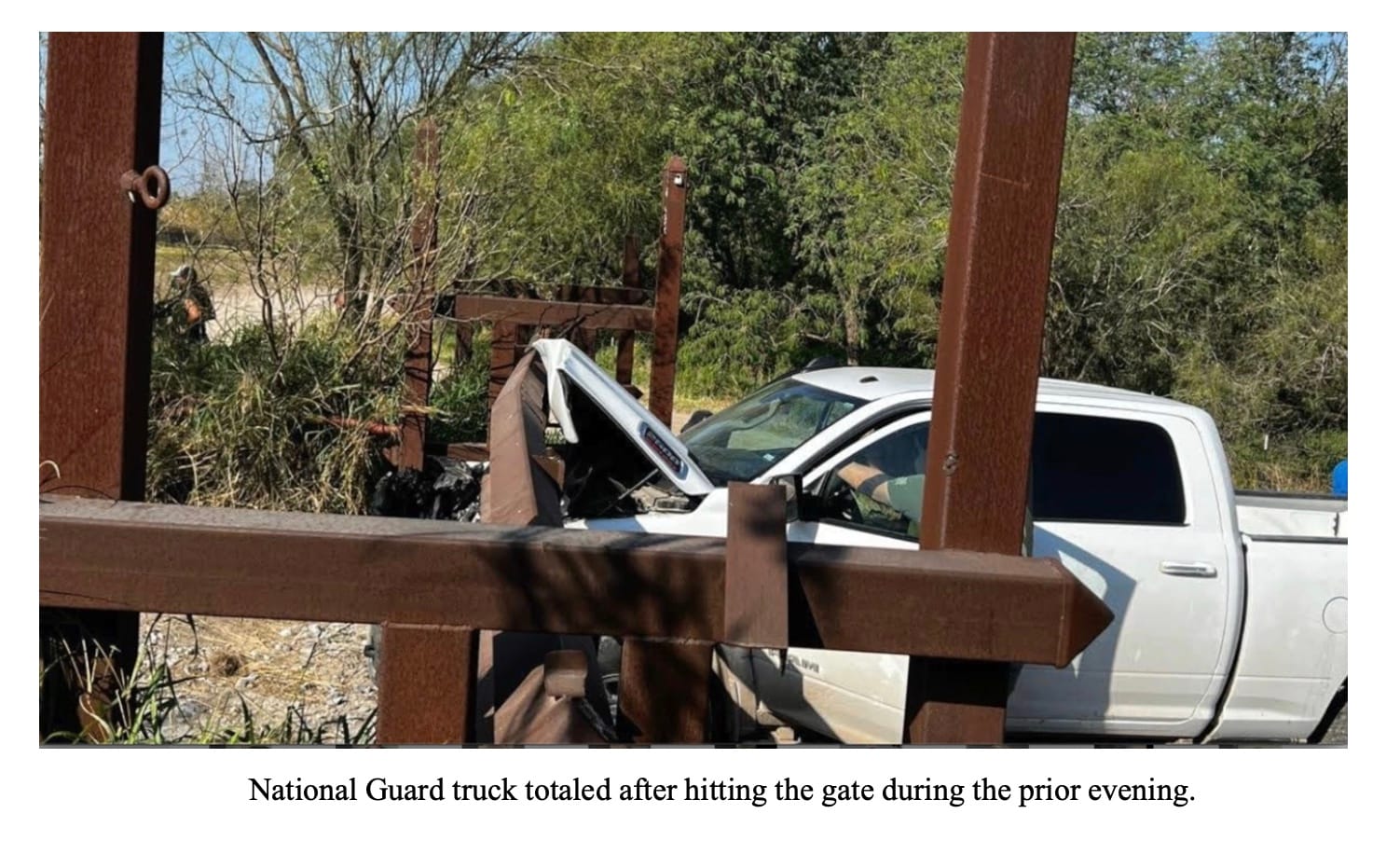

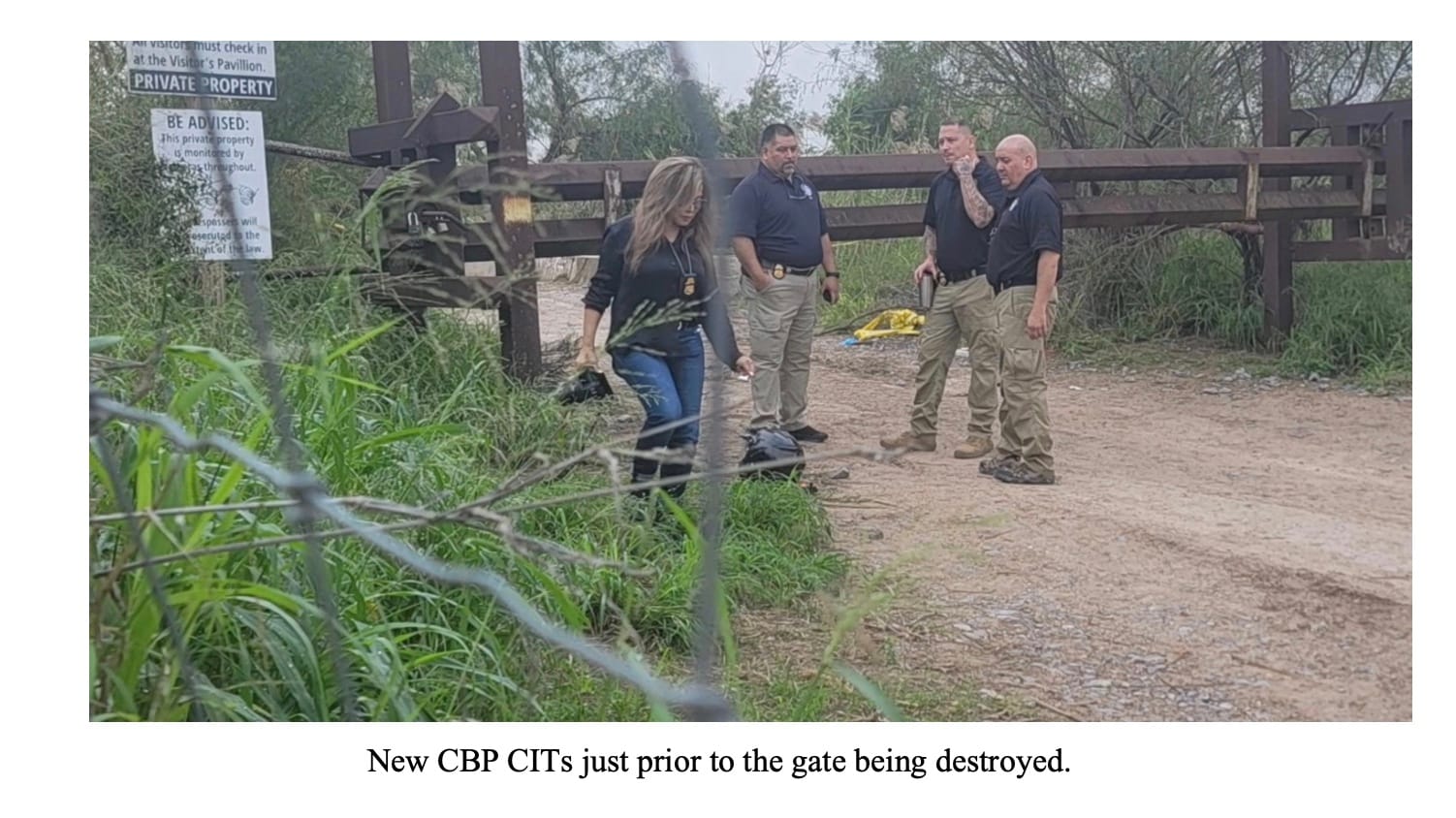

When Border Patrol Agent Raul Gonzalez was patrolling the border in Mission, Texas in December of 2022 on his ATV, he hit a large steal gate installed by the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol.[59] This gate was notorious for causing accidents. The National Guard had even destroyed one of their trucks hitting it. This was because the Border Patrol refused to put any reflector tape or paint on the gate in accordance with local laws, choosing instead to let leave it difficult for people to see in the dark.

BPCIT showed up in their new CBP black shirts and immediately tore the gate down. The agents’ family was given a nice pay out for an on-duty death, and the agency walked away from accountability.

10) Conclusions:

Border Patrol management has often stated that the only reasons these teams ever existed was because many uses of force occurred out in desolate areas. This contradicts the fact that the teams were created for cases that occurred within Imperial Beach’s city limits. It also does not account for cases like Valeria’s, Anastasio’s, Jose Antonio’s and countless others. Another excuse given was that many small border investigative agencies did not have the resources to investigate. This does not make any sense considering the Border Patrol had no authority to start the teams in the first place.

The practice of using BPCIT units to investigate critical events involving Border Patrol agents whether they are on duty or off continues today because no one has been held accountable. Failures to report, to secure and gather evidence, to secure the scene, to separate those involved, to notify investigative agencies in a timely manner, to provide them with the names of agents involved can be found in nearly every critical incident. The agency uses their sector BPCIT units to sit in on interviews of witnesses and perpetrators conducted with investigating agencies. They send BPCIT agents to attend autopsies and gather medical records of which they have no legal right or authority to, especially when considering it is their agency that is the subject of the investigation. This information that they gather is often leaked to the press to paint the victim as a drug user, mentally disabled or as having pre-existing conditions that may have attributed to the death.

It is no wonder that out of the hundreds of deaths that occurred at the hands of Border Patrol agents since 1987, not a single agent has been convicted or been held accountable. Families of these victims have been left with unanswered questions as they were never even given the dignity of a fair investigation as the law dictates. Other victims of these agents, those who’ve survived, suffer the same as those who did not because the BPCIT was involved in them all.

The BPCIT’s purpose is to interfere with the investigation, destroy and hide evidence, intimidate witnesses, spy on investigations and report back to sector management. Sector then coordinates with D.C. management on how to handle the press and those investigating. It is a secret unit in that it is never written about in CBP or Border Patrol public manuals and great lengths have been taken to keep their existence hidden. Their activities, investigations and reports are almost never made public, and the agency demands courts label them as law enforcement sensitive so that researchers cannot find them in databases. They are accountable and reviewed only to those in management directly above them at the sector level. This means they are a secret investigative team conducting secret investigations.

The existence of these BPCIT units in Border Patrol sectors and the actions they have taken for decades is how the agency has been able to claim that every single shooting has been justified. It is how they can claim that so few complaints are ever substantiated. The US Border Patrol has used the BPCIT to obstruct and deny justice to those it kills, rapes, tortures and abuses. The BPCIT has violated federal law by investigating crimes it does not have the authority to investigate. The relationships these agents and the sectors have maintained through the BPCITs with county, city, state and other federal law enforcement agencies that are required by law to help maintain accountability over the agency has perverted and denied justice to hundreds if not thousands of victims. Every case touched by this unit must be reviewed and reconsidered.

While the Border Patrol and CBP have claimed that these teams were needed out of desperation and the lack of resources, they refuse to address how they managed to cobble together enough resources to create large and robust BPCIT units.

BPCITs and their illegal actions violate:

· The US Constitution’s preamble that declares “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of happiness.”

· All state laws relating to rights to life and investigations.

· The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ American Declaration of the Rights and Duties to Man,

- Article I – Rights to life, liberty and personal security.

- Article II – Rights to equality before the law.

- Article XVIII – Right to a fair trial.[60]

· The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ American Convention,

- Article 1 – Obligation to respect rights.

- Article 4 – Right to life.

- Article 5 – Right to humane treatment.

- Article 7 – Right to personal liberty.

- Article 8 – Right to a fair trial.

- Article 10 – Right to compensation.

- Article 24 – Right to equal protection.[61]

NOTES:

[1] “Borderland Talk with Jenn Budd.” Substack. https://jennbudd.substack.com/p/my-official-border-patrol-records.

[2] “Deaths by Border Patrol,” Southern Border Community Coalition, Retrieved September 3, 2020, https://www.southernborder.org/deaths_by_border_patrol.

[3] “Not guilty: Jury acquits Border Patrol agent Lonnie Schwartz of involuntary manslaughter,” Tucson.com, November 22, 2018. https://tucson.com/news/local/not-guilty-jury-acquits-border-patrol-agent-lonnie-swartz-of-involuntary-manslaughter/article_80be72e4-ed96-11e8-9c42-47dbfc620c32.html.

[4] “Request for congressional investigations and oversight hearings on the unlawful operation of the U.S. Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams (BPCITs).” Southern Border Community Coalition, October 27, 2021. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/alliancesandiego/pages/3292/attachments/original/1635367319/SBCC_letter_to_Congress_Final_10.27.21.pdf?1635367319

[5] “Oversight and Homeland Security Chairs Request Information from Customs and Border Protection on Potential Misconduct of Specialized Teams.” Washington DC, US House of Representatives, January 24, 2022

[6] “Critical Incident Response Transition and Support,” Customs and Border Protection, Commissioner Chris Magnus. May 2, 2022.https://assets.nationbuilder.com/alliancesandiego/pages/409/attachments/original/1651850948/Critical_Incident_Response_Signed_Distribution_Memo_%28508%29.pdf?1651850948

[7] “United States Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams Complaints #002687-22-CBP.” (and #003204-22-CBP) Department of Homeland Security, Compliance Branch, Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Director Dana Salvano-Dunn. February 4, 2022. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/25872880-2022020420crcl20retention20memo20to20cbp20-20usbp20critical20incident20teams20e2809320redacted-508/

[8] 6 U.S. Code § 211, “Establishment of U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner, and operational offices.” Cornell Law School. Retrieved September 27, 2025. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/6/211

[9] “Handbook of Occupational Groups and Families.” US Office of Personnel Management. December 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2025. (113) https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/classifying-general-schedule-positions/occupationalhandbook.pdf

[10] Id. (109)

[11] 8 U.S. Code § 1357, “Powers of immigration officers and employees.” Cornell Law School. Retrieved September 27, 2025. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1357

[12] Maria Del Socorro Quintero Perez, Brianda Aracely Yanez-Quintero, Camelia Itzayana Yanez-Quintero, and J.Y., a minor vs. Dorian Diaz and Michael Fisher, Border Patrol Chief, et al., No. 13CV1417-WQH-BGS, U.S. District Court for Southern California, March 31, 2017, Pacer.com.

[13] Gonzales, Adolfo EdD, “Historical Case Study: San Diego and Tijuana Border Region Relationship with the San Diego Police Department, 1957-1994” (1995). Dissertations. 613. https://digital.sandiego.edu/dissertations/613

[14] Id. (126-134)

[15] “Use of Force Handbook.” US Customs and Border Protection, Office of Training and Development, HB 4500-01B, October 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2025. https://www.aila.org/library/cbp-october-2010-use-of-force-policy-handbook

[16] “U.S. Customs and Border Protection Use of Force Review,” CBP.gov, February 2013, https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/PERFReport.pdf.

[17] “CBP Use of Force Handbook, 2014,” CBP.gov, retrieved September 20, 2020, https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/UseofForcePolicyHandbook.pdf.

[18] Peralta, Eyder. “Border Patrol releases new use of force guidelines, critical report.” NPR, May 31, 2014. https://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/05/31/border-patrol-releases-new-use-of-force

[19] Maria Del Socorro Quintero Perez, Brianda Aracely Yanez-Quintero, Camelia Itzayana Yanez-Quintero, and J.Y., a minor vs. Dorian Diaz and Michael Fisher, Border Patrol Chief, et al., No. 13CV1417-WQH-BGS, U.S. District Court for Southern California, March 31, 2017, Pacer.com.

[20] Treviso, Perla. “Jurors of different minds in border shooting.” Arizona Daily Star, April 29, 2018. (A1, A6.)

[21] Trevizo, Perla. “Closing arguments possible Mon. in border fence killing.” Arizona Daily Star, April 15, 2018. (C1, C6).

22]“Killing of Valeria M. Tachiquin still unresolved after 3 years.” Southern Border Community Coalition, July 14, 2017. https://www.southernborder.org/killing-of-valeria-m-tachiquin-still-unresolved-after-3-years

[23] Cochise County Sheriff Office Report for Incident #22-03910. May 10, 2022. Supplement by Detective J.C. Hoke. (4).

[24] USA v. Lonnie Swartz, No. 15-cr-01723-RCC-DTF-1. US District Court, District of Arizona, Tucson Division. Significant Incident Report #13-TCANGLE-101112000012(4). Pacer.com.

[25] Id. Testimony of Roy Pierce. (15)

[26] Id. Testimony of Gerardo Carranza. (14-15)

[27] Id. Testimony of Michell Terwilliger.

[28] San Diego County Sheriff’s Department, Case# 13165829, Report# 13165829.1, Event # E1333152, Detective Hector Fuentes (SH5861). December 25, 2013.

[29] USA v. Lonnie Swartz, No. 15-cr-01723-RCC-DTF-1. US District Court, District of Arizona, Tucson Division. Significant Incident Report #13-TCANGLE-101112000012(4). Pacer.com.

[30] Id. Testimony of John Zuniga.

[31] Steller, Tim & Trevino, Joseph. “Nogales crowd pelted officers with rocks after drug drop, agency says.” Arizona Daily Star, October 12, 2012. (A1, A4)

[32] O’Dell, Rob. “Aftermath of border shooting detailed.” Arizona Republic, July 26, 2016. (1A, 10A)

[33] “Request for congressional investigations and oversight hearings on the unlawful operation of the U.S. Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams (BPCITs).” Southern Border Community Coalition, October 27, 2021. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/alliancesandiego/pages/3292/attachments/original/1635367319/SBCC_letter_to_Congress_Final_10.27.21.pdf?1635367319

[34] Ibid.

[35]“Death on border: Shocking video shows Mexican immigrant beaten and tased by Border Patrol agents.” Democracy Now!, April 24, 2012. https://www.democracynow.org/2012/4/24/death_on_the_border_shocking_video

[36] “Witness to deadly shooting by Border Patrol agents disputes official account.” 10 News, November 21, 2012.

[37] Cochise County Sheriff Office Report for Incident #22-03910. Detective J.C. Hoke addendum, May 10, 2022. (12)

[38] Trevino, Joseph. “A year later, family seeks answers to fatal shooting in Nogales.” Arizona Daily Star, December 3, 2012. (A2, A8)

[39] USA v. Lonnie Swartz, No. 15-cr-01723-RCC-DTF-1. US District Court, District of Arizona, Tucson Division. John Zuniga testimony. Pacer.com.

[40] USA v. Lonnie Swartz, No. 15-cr-01723-RCC-DTF-1. US District Court, District of Arizona, Tucson Division. Gary Rini testimony. Pacer.com.

[41] Estate of Anastasio Hernandez-Rojas et al v. United States of America et al, No: 11-cv-00522-L-BLM. US District Court, District of Southern California, San Diego. San Diego Police Department Homicide Report Detective D. Collins, I.D. 5303, report prepared on 6/17/10 & Sergeant David Dolon, I.D. 4332, report prepared on 6/3/10.

[42] Id. Addendum II, D. Collins, #5303, July 9, 2010.

[43] Id. Detective D. Collins, I.D. 5303, report prepared on 6/17/10 & Sergeant David Dolon, I.D. 4332, report prepared on 6/3/10.

[44] Id. San Diego Police Department Homicide Report.

[45] Cochise County Sheriff Office Report for Incident #22-03910. May 10, 2022. Detective Hoke – supplement added, BPA Staheli interview. (22).

[46] USA v. Lonnie Swartz, No. 15-cr-01723-RCC-DTF-1. US District Court, District of Arizona, Tucson Division. Gerardo Carranza testimony, (8). Pacer.com.

[47] Id. (8)

[48] Id. (30)

[49] Id. (33)

[50] Id. (49)

[51] Id. (54)

[52] Id. (55)

[53] Id.

[54] Id. (61-62)

[55] Ainsley, Julia. “What happened to Ray? Family of Native American man killed by Border Patrol in Arizona wants to know why he was shot.” NBC News, June 1, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/family-wants-know-why-border-patrol-agents-shot-ray-mattia-rcna87113

[56] “Tucson agents involved in fatal shooting of man, while responding to shots fired call.” Customs and Border Protection Press release, May 22, 2023. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/tucson-agents-involved-fatal-shooting-man-while-responding-shots

[57] CBP video. https://www.dvidshub.net/video/887917/use-force-incident-ajo-arizona-may-18-2023

[58] “The Magic Wand.” Episode 463. The Green Line Podcast. May 27, 2023. https://www.podchaser.com/podcasts/the-greenline-43984/episodes/episode-463-the-magic-wand-174087397

[59] Yanez, Alejandra. “US Border Patrol agent on ATV dies in accident while on duty.” NBC 23, December 7, 2022. https://www.valleycentral.com/news/local-news/u-s-border-patrol-agent-dies-in-accident-while-on-duty/

[60] “American Declaration of the Rights and Duties to Man.” Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basics/declaration.asp

[61] “American Convention on Human Rights.” Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basics/convention.asp