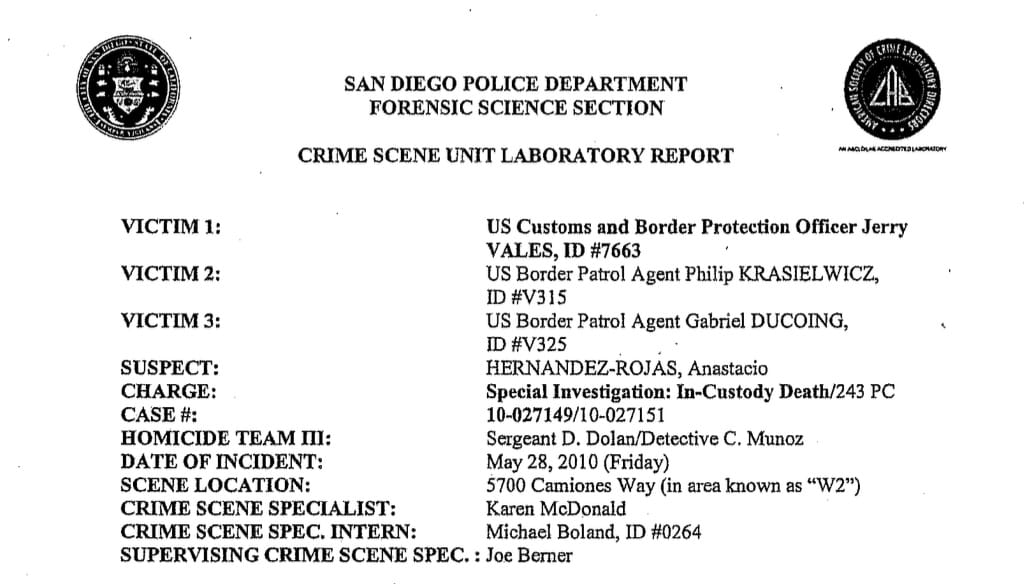

The killing of Anastasio Hernandez Rojas & subsequent coverup by former Chief Rodney Scott’s illegal & secret Critical Incident Team.

This action by former Chief Scott delayed the SDPD Homicide investigation and further obstructed their efforts. Scott is now the Commissioner of CBP in the second Trump Administration.

This article is part of Borderland Talk’s Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams (CIT) series documenting the acts of the illegal and secret coverup units that still exist under their parent agency, Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR). To read other articles and see the history of the coverup teams, see the Critical Incident Teams newsletter in the blog section.

Please note this article only addresses the actions of the San Diego Sector Border Patrol CIT unit and not the many other aspects of the case. Remember: Border Patrol CITs were and are still not legal. They were never authorized by Congress. The Border Patrol does not have the legal authority to investigate their own use of force incidents and is in fact, expressly forbidden from doing so, as I have covered in other articles. Border Patrol CITs are coverup teams and continue unabated within CBP. No cases investigated by CBP-OPR should ever be considered legal or truthful by any court of law because the federal government refuses to address this systemic and institutionalized corruption within CBP and the US Border Patrol.

This article and the court documents required to research and write it, was made possible by subscribers like you. Thank you!

Summary:

Anastasio Hernandez Rojas was forty-two years old when he made a fateful decision one evening to five-finger some food for his family. As an undocumented pool skimmer and tiler with a wife and five US born children, Anastasio had lived in the San Diego area for over twenty years, struggling to make ends meet in a system that needed his labor and shunned him at the same time. He was arrested, turned over to the Border Patrol and sent back to Mexico.

On the evening of May 28, 2010, Anastasio and his brother Pedro crossed the border illegally (without inspection at a port of entry) in hopes of returning to his wife and children. They were apprehended by Border Patrol and turned over to a private transportation service without incident and then taken to the Chula Vista processing station. It was here that the story of Anastasio’s death began when Border Patrol Agent (BPA) Gabriel Ducoing kicks the father’s legs out during a routine search.

When BPA Ducoing kicked Anastasio’s feet apart to search him, he damaged his ankle that had a surgical pin permanently placed in it from a previous surgery. BPA Ducoing admitted to having kicked Anastasio’s legs apart but claimed that he had not injured him and that he was faking the injury. Other agents in processing that evening admitted that Anastasio had complained about BPA Ducoing hurting him. Additionally, though there was no audio included, the processing center camera footage showed Anastasio sitting on a bench, massaging his ankle and repeatedly pointing to it while talking with various agents.

Supervisory Border Patrol Agent (SBPA) Ismael Finn was called in to deal with Anastasio’s complaint as was Customs and Border Protection policy, but he denied his request to see a doctor. SBPA Finn claimed in his interview that he was never told of the incident and that the only reason he had ordered Anastasio to be immediately “voluntarily returned” to Mexico was because he was loud and aggravated. This statement contradicted the other agents’ statements who were present including the assaulting agent, BPA Ducoing. SBPA Finn further stated that he was concerned that Anastasio might disturb or hurt other detainees even though the processing center was nearly empty that evening.

From my experience with these situations, SBPA Finn ordered that Anastasio be taken to the port of entry for an immediate voluntary return to Mexico because he did not want to file the report for his medical evaluation or deal with an internal affairs investigation into the complaint. His exact motivations are unknown of course, but it is clear that CBP policy, state, federal, and international laws dictate that anyone complaining of an assault in custody is to receive an investigation. One must wonder that if this had happened, would Anastasio still be alive today.

BPAs Ducoing and Philip Krasielwicz drove Anastasio to the San Ysidro port of entry that evening for a “forced” voluntary return as they left his brother at the Chula Vista processing station. At an area known as W-2 (pronounced whiskey-two), the agents attempted to force a handcuffed Anastasio through a gate that led back to Mexico. According to the Border Patrol, this was when Anastasio suddenly became violent and refused to return.

In short, BPAs Ducoing and Krasielwicz claimed to be the victims of Anastasio’s rage. They claimed he was not handcuffed when the agents were joined by two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, Harinzo Narainesingth and Andre T. Piligrino. With Anastasio still on the ground, the four agents beat, punched and kicked him. They kneeled on his neck and back. As witnesses gathered and began videoing the incident with their cell phones, the agents drug Anastasio’s body further away from witnesses to hide their actions.

In all, twenty-seven other officers from CBP, Border Patrol, ICE and Paragon Security services responded to the scene. Twelve CBP, ICE and Border Patrol agents surrounded Anastasio in a Rodney King fashion. They kicked, punched, whacked his body repeatedly with their steel batons and kneeled on his back and neck while he begged for mercy, for God, for his mother. As Anastasio laid in the fetal position on the ground, BPA Krasielwicz walked up and stripped his pants off his body to further shame the man. The agent could be seen in a video calmly folding Anastasio’s pants and placing them in his car. The trophy pants were never recovered.

At this point, CBP Officer Jerry Vales can be seen and heard yelling, “STOP RESISTING!” He then fires the first of many tasers at Anastasio. Vales and other CBP officers later disagreed with the Border Patrol’s version that Anastasio was not handcuffed. CBP claimed that Anastasio was in fact handcuffed but still claimed that Vales and the other officers were the real victims. Agents could be heard threatening witnesses to “KEEP ON WALKING!” They claimed that after Anastasio’s first beating by the ICE and Border Patrol agents, he was able to “crab-walk” while handcuffed and then launched his body through the air landing karate style kicks onto the back and shoulders of CBP Officer Vales.

The video did not show this amazing act, because it did not happen. There was no evidence on Vales’ body of such violence as the SDPD Homicide detectives discovered. The video did show a handcuffed Anastasio lying in the fetal position as CBP Officer Vales tased him at least four times. Standard tasing training policy requires a five second maximum. Anastasio received two tasings for over ten seconds, one of which was a direct tasing to his heart. This was what finally stopped his heart. Paramedics then pumped him full of drugs to restart it, but his brain did not survive and he passed on May 31, 2010.

While the family and their attorneys would later win a monetary settlement, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights found in 2025 that the United States and then San Diego Border Patrol management used the illegal and secret coverup team known as Critical Incident Teams to obstruct justice and prevent agents from being held accountable.

None of the agents or officers involved in Anastasio’s killing that day ever faced any discipline. The Border Patrol chief involved in ordering the teams’ actions was Rodney Scott, the current CBP Commissioner.

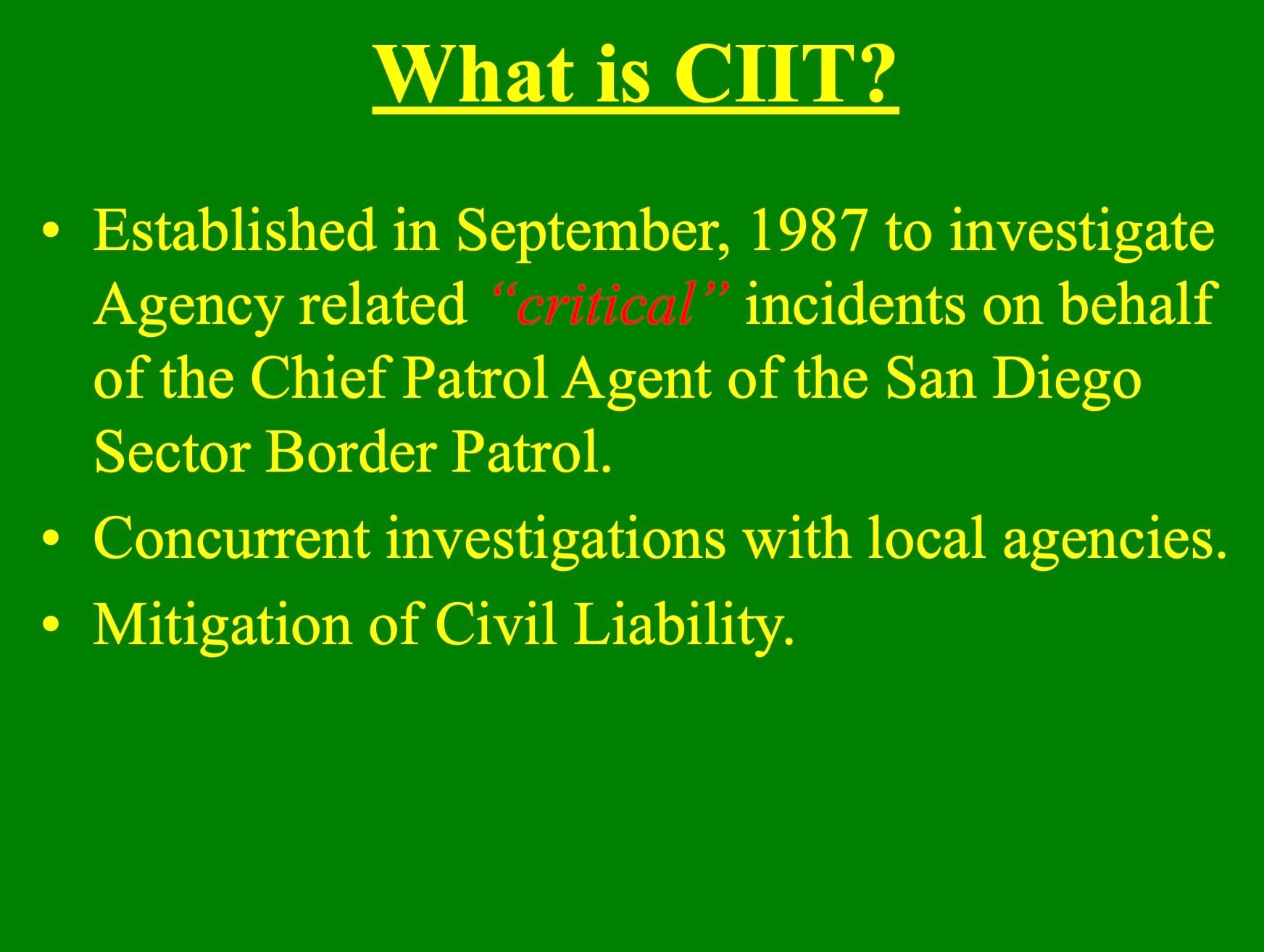

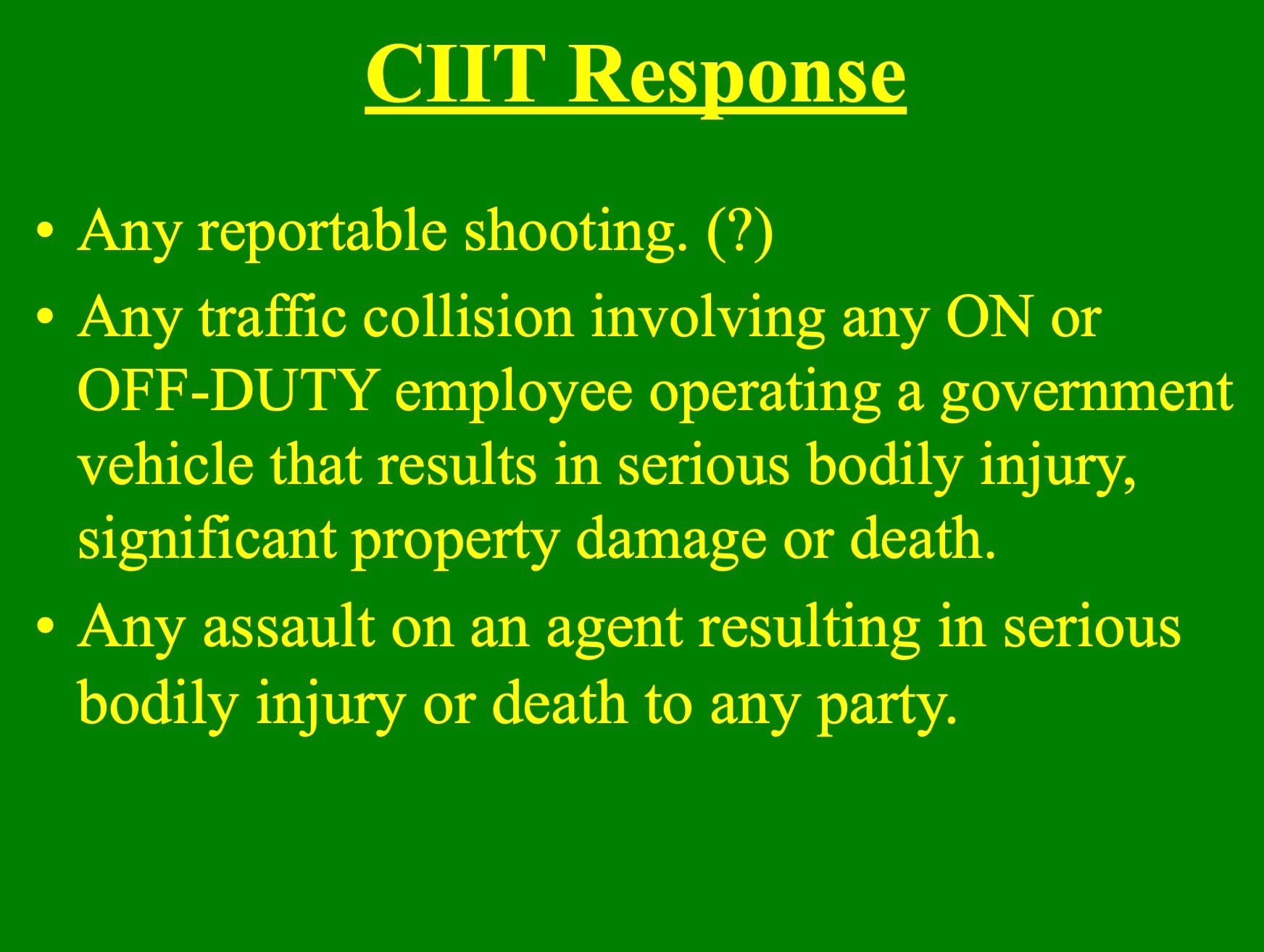

Note: The San Diego Sector Critical Incident Team was called the Critical Incident Investigative Team or CIIT. Readers will see this name and acronym on documents. Because some sectors have different names for their coverup teams, all the teams are referenced as Critical Incident Teams or CITs in my writings. To learn about how the teams started and the various names of teams, please see this declaration for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Critical Incident Team Pattern and Practice:

Anastasio’s case is one of the best examples I have analyzed of how the Border Patrol used the illegal CIT units to obstruct justice and spy on investigative agencies in order to control the investigations into its agents and their crimes. The direct result of the CIT’s actions denied the family their right to a fair and unbiased investigation as well as equal protection under the law. The CIT units secretly designed by San Diego Sector Border Patrol in 1987 had developed into a robust and systemic pattern of obstructing justice by 2010 when Anastasio was killed. Through my years of investigations into the teams, I have identified patterns and practices the teams generally followed.

- It is policy to call the CIT units first before the real use of force investigators show up.

The CBP and Border Patrol 2010 Use of Force Handbook applicable at the time of Anastasio’s killing was law enforcement sensitive. This meant that it was not public. The handbook stated in Chapter 5 that agents were to call these teams to begin a “parallel investigation into an incident via a Critical Incident Team (CIT), but the respective CIT investigation will be the secondary investigative entity for investigative purposes. The CIT will coordinate with the primary investigative entity to ensure procedural continuity throughout the investigation.”

But verbal orders given in supervisor trainings and known throughout the agency were that agents were to always call the CITs first. CITs would make sure the evidence matched the Border Patrol’s official account and would then coordinate with management to present their version of events to the actual use of force investigators be they local, state or federal agencies. While the CITs presented themselves as aides or liaisons to these investigators, in reality they were deciding what was evidence and what was not by being the first to the scenes. This illegal action then reverberated throughout all parts of the case ensuring no agent or officer would be held accountable.

The Anastasio killing demonstrated this policy expertly. It was documented in the San Diego Police Department’s lawful homicide investigation that it was the San Diego Sector Dispatch was the one to notify the CIT. Based on dispatch records, CIT was notified on May 28, 2010 at 2228 hours. They then notified the San Diego Sector Press Information Officer Juan Ramirez that Amy Isaacson of KPBS Radio was calling about the event just four minutes later at 2232 hours. Dispatch then called the Press Information Office again six minutes after the first call at 2238 hours and relayed the same information to Press Information Officer Mike Hernandez.

This means that the CIT units were not just a liaison with the real use of force investigators like Border Patrol always suggests. If sector dispatch knew to call CIT and the press office before calling any outside investigators, that suggests this is policy, pattern and practice. If the CIT units were just creating duplicate reports of investigations for administrative purposes as former Border Patrol Chief Michael Fisher testified to in Maria del Socorro Quintero Perez et al v. Dorian Diaz & US (#13cv1417-WQH-BGS), then why are they the first being called to the scenes? [1]

Border Patrol’s other excuse for having these illegal teams is that they were only used for incidents in desolate areas that the investigators could not reach. The Anastasio case, like many others, shows that these illegal teams were used in densely populated areas such as ports of entry and within city limits.

The 2010 Use of Force Handbook further stated that the agent in charge of the scene or reporting officer referred to as an RO, “…shall ensure that the incident has been reported to the law enforcement authorities having jurisdiction over the investigation.” In the Anastasio case, this agency was the San Diego Police Department (SDPD). The designated RO in this case was Supervisory CBP Officer Ramon De Jesus according to the Use of Force Report he personally filled out.

No one at CBP or Border Patrol ever notified the SDPD of the incident. SDPD reports documented that they only became aware there was a use of force incident once a local KPBS reporter had called them the following day on the 29th to find out the status of the investigation.

In violation of CBP policy, San Diego Border Patrol management failed to call all other agencies with authority in a timely matter San Diego Police Department, Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General and the Federal Bureau of Investigations. (Customs and Border Protection’s Internal Affairs did not start until 2012 and ended in 2014. Customs and Border Protection’s Office of Professional Responsibility did not exist until 2016.) The illegal Border Patrol CIT agents had control of the crime scene for at least fifteen hours after the incident. SDPD was notified by the media who told them of the beating and tasing.

- CITs are responsible for setting and controlling the narrative.

When SDPD homicide investigators called the port of entry to ask if there was an incident, they were given a summary of the situation that reflected what CBP and Border Patrol wanted them to know about the case. The story they settled on after fifteen hours was that Anastasio was a man of superhuman strength who had somehow overwhelmed all the agents who were present during the incident.

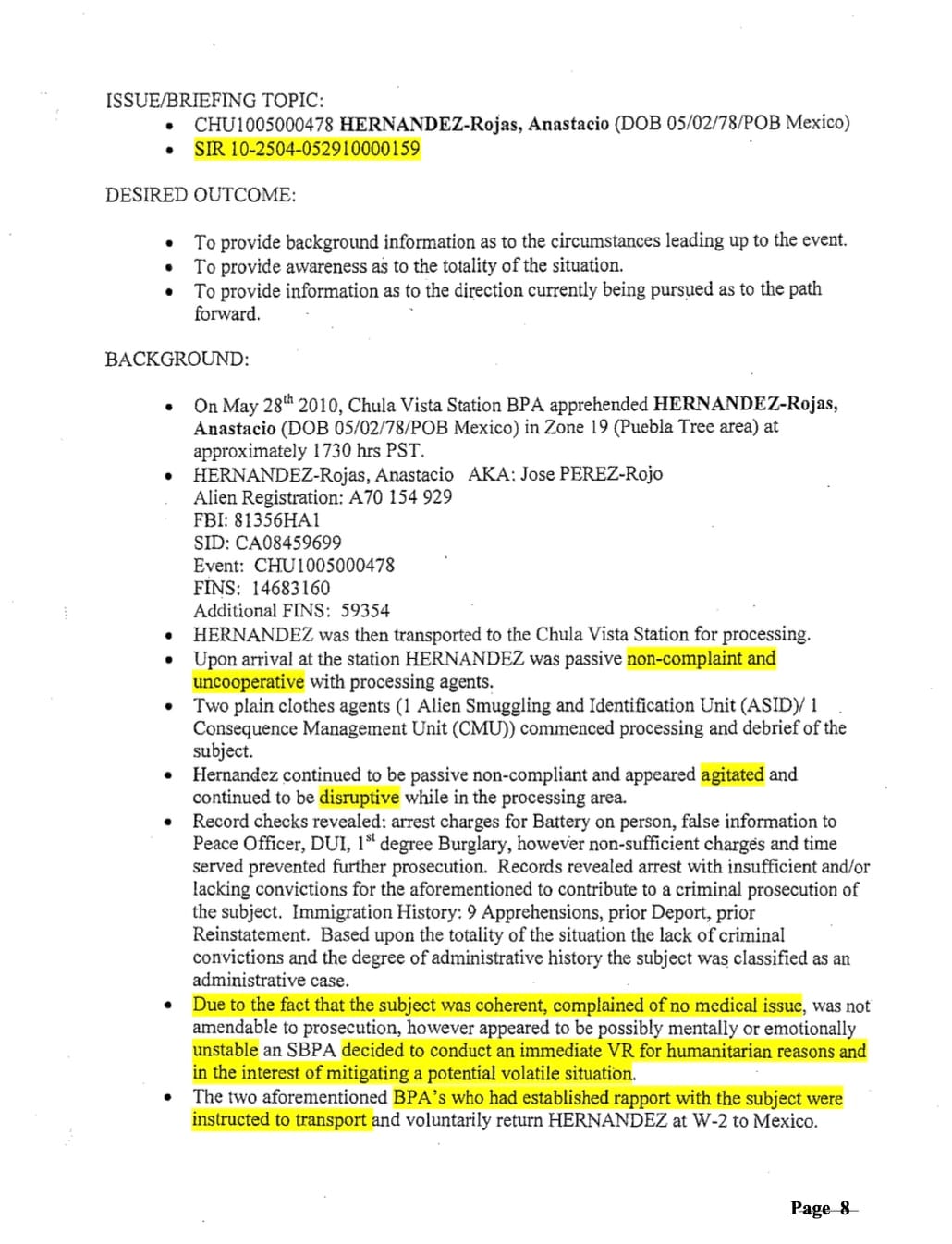

The briefing by then Assistant Patrol Agent in Charge Ryan S. Yamasaki of the Chula Vista Station showed that the information given to SDPD failed to mention the first assault upon Anastasio by BPA Ducoing on May 28th at the Chula Vista processing center. They simply told the SDPD Homicide investigators that Anastasio was “non-compliant and uncooperative with agents in processing.” Once Anastasio was taken to the port, the briefing stated that Anastasio attacked the agents and that once tased, he continued to fight and strike agents. After three tasings, Anastasio stopped breathing according to the briefing.

Assistant Patrol Agent In Charge Yamsaki of Chula Vista Border Patrol instructs San Diego PD Homicide Investigators on what the evidence should be in the first briefing. the Anastasio case.

There was no mention of the fourth tasing.

APAIC Yamasaki listed off past charges against the victim to let investigators know that they believed Anastasio was a violent criminal. He admitted that the Border Patrol also called in the SIG unit, Smuggling Interdiction Unit even though this incident had nothing to do with smuggling. This is because in the San Diego Sector, the SIG unit is still used as a secondary CIT, similar to the Sector Intelligence Unit (SIU). Both units have CIT training and can act as illegal CITs whenever the CIT is unavailable. These units continue to act as CITs today although technically the CITs have been legalized under CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility by the Biden Administration.

By 2230 hours on May 29th, the briefing stated that Border Patrol was looking to charge Anastasio with assaulting the agents. The SDPD Homicide unit complied with this request.

SDPD Homicide Investigators immediately charge Anastasio with assaulting federal officers without conducting any investigation and issue a press release in accordance with Border Patrol’s narrative.

Although the investigation should have centered on the use of force used against Anastasio, SDPD Homicide investigators tailored their questions to determine why it was that he attacked the agents. This is quite extraordinary since it was Anastasio who was lying in the hospital covered with bruises from head to toe and none of the agents involved had so much as a scratch on them. The words of the agents were taken as fact even though the evidence was plainly stating otherwise. When they interviewed Anastacio’s brother, Pedro, they asked him whether his brother may have been on drugs, alcohol or had a mental disorder that would cause him to become violent. They came back to these questions again and again as if Pedro was lying about his brother’s possible drug use. Pedro kept insisting that Anastasio did not use drugs.

- CITs act as evidence collection teams for investigating agencies instead of those agencies using their own agency’s professionally trained and certified teams.

SDPD Homicide investigative reports stated that when they finally arrived the following day, May 29th, the scene had been left unsecured throughout the evening and taser prongs were scattered around. All agents who were involved in the incident were unknown to the SDPD investigators as they had not received a list of agents nor witnesses from either the CBP or the Border Patrol. Some of the agents who were present were only discovered after later interviews revealed their involvement. For example, SDPD Homicide detectives discovered that CBP Officers Victoria Guzman and Heather Ramos were present and involved in dispersing witnesses before statements could be obtained only after they had interviewed witness and Mexican Immigration Agent Raphael Barriga-Pulido on June 11th, two weeks after the killing. [2]

This was a clear obstruction of justice and tampering of evidence.

This failure occurred with other witnesses as well because CBP Officer Jerry Vales (the officer who tasered Anastasio four times) called out over the radio for other CBP officers to respond to the area and force witnesses to leave. Supervisory CBP Officer Ramon De Jesus, the assigned reporting officer or RO, even admitted in his interview with detectives that he had taken peoples’ phones and erased pictures and videos of Anastasio’s beating before making witnesses leave the area. [3] All of the witness statements confirmed this. Years later, when De Jesus was questioned in the civil case brought by Anastasio’s family, he refused to answer the same questions and exercised his right to not incriminate himself by pleading the 5th Amendment.

Only a few witnesses that had been ushered out of the area by agents were later identified and interviewed by SDPD Homicide investigators but only because they contacted the department themselves or the family’s attorney. These witnesses stated that there were likely more than a dozen other witnesses. SDPD Homicide investigators were never able to locate most of these witnesses because of the actions of CBP officers and Paragon Security Services.

One witness, Ashley Young, was able to evade CBP and Paragon Security officials as they destroyed evidence, but she was never even interviewed by SDPD Homicide investigators. Her testimony was only available in the civil case two years later because the family’s attorney located her. Her video of agents beating Anastasio to death was never even viewed by SDPD Homicide. [4] The order to disperse witnesses and erase evidence from their phones arguably enabled the agencies to destroy evidence and thus obstruct justice.

Whatever evidence that may have existed on the uniforms and bodies of the agents and officers involved was destroyed as well when all were allowed to leave and return to their homes. SDPD Homicide did take pictures of some of the agents, but that was after they had changed their clothing and showered. None of the agents involved showed any signs of being hit or kicked by Anastasio as they reported later in their interviews with the detectives. The uniforms worn by these agents were not recovered.

The unmarked, white truck that Border Patrol Agents Ducoing and Krasielwicz transported Anastasio in to the San Ysidro port of entry was never processed by SDPD for evidence. The beating could have reasonably started in the ride down to the port since it was BPA Ducoing who first assaulted Anastasio and who was in danger of receiving a complaint and investigation. But we will never know that, because no one bothered to secure the truck.

The marked Border Patrol truck, M94333, that agents attempted to shove Anastasio in during the middle of the incident, was only located days after and had not been secured. Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Avila admitted allowing another agent use the vehicle in the next shift but claimed he told him not to wipe off a smear left by Anastasio. SBPA Avila could not say for sure if he had put anyone in the back of the truck during his shift. SDPD Homicide interviewed the agent who assured them he had not put anyone else in the back of the truck and left it parked at the Chula Vista Border Patrol Station. SDPD forensics processed the truck on May 29th, at approximately 2010 hours, nearly 24 hours after the incident. [5]

The chain of custody of the vehicle was broken. Since agents had already demonstrated they were willing to cover-up and destroy evidence from the start of this case, assurances that the truck had not been touched in the back fall flat and cannot be trusted.

The autopsy report from Sharp Chula Vista Hospital showed that Anastasio was brought in from the ambulance with only one shoe and a wallet. In one of the witness videos, one can clearly see that BPA Krasielwicz ripped off Anastasio’s pants leaving him cuffed on the ground as agents continued to beat him. I can only assume this was done to further humiliate Anastasio as there was no safety reason for this action. The whereabouts of the rest of his clothing, including the pants were never noted in the SDPD Homicide investigation files. It was reported that CIT Border Patrol Agent Joe Vaiasuso collected two taser probes from a hospital tray at 2356 hours on May 28th. Emergency room doctors had reportedly “removed them from clothing worn by” Anastasio according to Vaiasuso. Where these “clothes” ended up was never stated in the reports. [6]

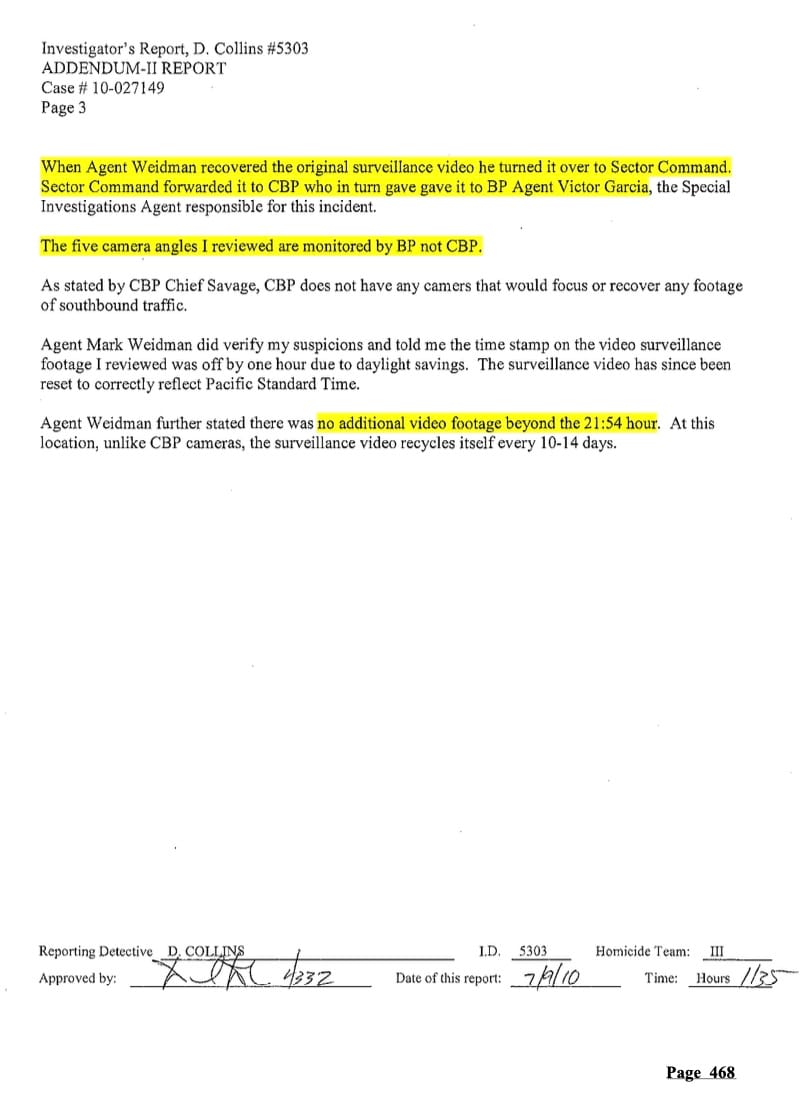

The video evidence captured by port cameras and secured by BPA Weidman was given to the Border Patrol CIT agents. SDPD Homicide Detective D. Collins documented in an addendum that BPA Weidman told him that CIT BPA Victor Garcia had been given the video and that CIT BPA Garcia and CIT Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Armando Gonzalez were in charge of the case. [6]

On June 9th, SDPD Homicide Detective Collins contacted and received a “copy” of the video evidence. After viewing, he noticed that he should have been able to see the incident but there was nothing on the tape. He discovered that the time stamp of the video was off by an hour. The video showed the same area but at an hour before they arrived with Anastacio in the unmarked white truck. Detective Collins contacted the CIT unit on June 10th, June 13th, June 29th and again on July 6th only to never receive the actual video of Anastasio’s beating. In one conversation, CIT BPA Garcia told the detective that the cameras may be CBP’s and suggested he ask the port. [7]

San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151 Investigator’s Report, Addendum II, D. Collins, #5303, July 9, 2010.

This run around wasted valuable investigation time, but there was also a more sinister reason for making the detective do so much leg work; agents knew the machines would write over the original tape in ten to fourteen days. It was common practice, even back when I was an agent in the late 1990s, for Border Patrol to use machines that wrote over the tapes in ten to fourteen days, sometimes thirty days. CIT cannot claim this was not intentional. This was their job, to collect the tapes and hand them over to investigating agencies. Waiting not only got rid of the evidence; it destroyed it without any agent having to lay a finger on it.

Detective Collins ended up speaking with BPA Wiedman one more time on July 7thonly to be told that he had given CIT BPA Garcia the tape and that if there was still a tape in the machine, it would have been overwritten by then. The addendum was well written, and times and dates were well documented. To me, as a former intelligence agent with investigative experience, Collins wanted this documented because he knew that the CIT was giving him the run around in order for the video evidence to be destroyed.

- CIT’s goal is to always portray the agents as the victims.

The first articles written about Anastasio’s beating and tasing were published on May 30, 2010, one day before the victim was taken off life support and passed. The Desert Sun stated that Border Patrol spokesman Daryl Reed declared that Anastasio had “become combative” and had to be tased. [8] This demonstrates how the CIT narrative is pushed out to the media through Border Patrol Press Information Offices.

On June 2, 2010, the Santa Maria Times announced Anastasio’s death. They quoted CBP spokesperson Jaqueline Dizdul that Anastasio “had become combatant” and that he “ignored repeated orders to stop fighting.” She further claimed that he was tased to “protect agents.” [9] The following day, SDPD Homicide Detective Collins fell in line with the CIT narrative and stated to the Los Angeles Times that Anastasio had become violent and needed to be subdued by tasing. [10]

When Anastasio was beaten and tased with his hands handcuffed behind his back, the narrative Border Patrol intentionally chose according to former CBP Commissioner of Internal Affairs James Tomsheck, was that he was not handcuffed behind his back even though he was and even though CBP’s official narrative stated he was handcuffed. This is because using lethal force on a person while their hands are handcuffed behind their back violates the use of force continuum. [11] It did not matter to the agency that this was not true or that it contradicted CBP’s statements because they believed at the time that they had confiscated or erased all witness videos.

Although the SDPD Homicide investigation proved that Anastasio was not violent and it was he who was the victim, the agency continues to claim today that its agents were the victims.

- CITs are to control and spy on the official investigations.

In order to know what evidence SDPD Homicide detectives were finding in the case and how to react publicly, Border Patrol CIT agents were dispatched to sit in on thirteen interviews. These interviews consisted of one with Anastasio’s brother Pedro and those interviews of Border Patrol agents that were done in the first twenty-four hours of the investigation once SDPD was notified.

Pedro was an undocumented immigrant who had just seen his brother kicked and injured by an agent. He witnessed them take him out of the Chula Vista processing facility. He was left in the processing center not knowing what had happened to Anastasio. The fact that SDPD Homicide detectives would allow Border Patrol agents to be present in the interview is more than just concerning. He was told by agents his brother became violent and was now in the hospital. Pedro would have had a valid reason to believe that if he spoke frankly, he might end up in the hospital just like his brother. He should have been removed from Border Patrol custody and interviewed in SDPD custody. Undocumented migrants are fearful of the Border Patrol. To be interviewed in their facilities and with agents wearing the same badge was clearly a threat.

CIT BPA Victor Garcia sat in on SDPD Homicide interviews with Chula Vista processing agents: BPA Sandra Cardenas, BPA Gabriel Ducoing, BPA Jose Galvan, BPA Philip Krasielwicz, BPA Robinson Ramirez and BPA Nicholas Austin. CIT BPA Garcia also sat in on SDPD detectives’ interviews with SBPA Edward C. Caliri, BPA Scott Carlson and BPA Derrick Llewellyn. CIT BPA Joe Vaiasuso sat in on interviews conducted by SDPD Homicide with Chula Vista processing agents BPA Christian Mitchell and SBPA Ismael Finn. CIT BPA Wendy Lee was also present at Pedro’s interview, and CIT BPA Mike Mannen was at BPA Ryan Reyes’ interview. [12]

The fact that CIT agents only sat in on interviews with Border Patrol agents and not CBP or ICE officers shows how the Critical Incident Teams are not concerned with truth or justice of the case, but with how the agency and its agents are perceived and their criminal and civil liability. As the San Diego Sector CIT powerpoint presentation from 2010 shows below, their purpose is to limit this liability and not to find the truth.

2010 San Diego Sector Critical Incident Team Powerpoint presentation.

Finally, it was former Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott who ordered the use of an administrative immigration subpoena to force the San Diego Medical Examiner to turn over the report to the CIT unit and not to the SDPD Homicide team as is custom. When SDPD detectives learned that the medical examiner had given the report to the CIT, they asked for Border Patrol to turn it over to them.

It is legally imperative that the official investigators have the actual signed report and not a copy. Chief Scott refused to turn over the report citing HIPAA medical records release laws that were not relevant to a homicide case. Furthermore, former CBP-Internal Affairs Commissioner James Tomsheck testified that the use of an administrative immigration subpoena for a medical examiner’s report was illegal. [13]

First, the Border Patrol had no legal right to possess a victim’s medical records, because it is an immigration agency and not an investigative agency. Second, it was an immigration subpoena which is not valid where medical records are concerned. Third, San Diego sector and Washington DC headquarters management used the report to claim that no one could be sure if Anastasio would have died from the beating and tasing by the agents if he did not have high blood pressure or an enlarged heart.

This argument would require we find no one responsible for murder if they can prove the victim had a pre-existing condition. This is ridiculous.

CIT and Border Patrol management also used the toxicology report to claim that Anastasio had “meth” in his body and that it could have led to his death. They failed to mention that the blood tests that were used were taken after paramedics had injected him with drugs to restart his heart and after the hospital had injected him with more drugs to keep him alive. None of this mattered though, because it was leaked to the press by the Border Patrol. Every story published on the incident after this came out, stated that Anastasio had meth in his system as if it were an undisputed fact. Obtaining the medical report was used by Border Patrol to create the narrative that the victim was violent. [14]

This action by former Chief Scott delayed the SDPD Homicide investigation and further obstructed their efforts. Scott is now the Commissioner of CBP in the second Trump Administration and thus has total control over the Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams and their agents since it was moved to CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility.

Conclusions:

Within hours of the incident, Border Patrol’s San Diego sector and Washington DC headquarters knew what the agents were saying had happened at the port of entry in San Diego. Because the supervisors failed to keep the agents involved in the beating and tasing separated and on duty until SDPD Homicide could interview them as CBP policy directed, they were able to gather together and align their stories. This can clearly be seen with the absurd statements of the CBP officers involved of how a handcuffed Anastasio, who was being tased at the time, was able to somehow “crab-walk” and then leapt through the air and kicking CBP Officer Vales in the back of his head, his back and shoulder. As stated above, SDPD Homicide found no evidence of this accusation.

This aligning of stories is done on every use of force incident and was done as a matter of routine during this one. Because the supervisors failed to stop witnesses and hold them for the SDPD investigators, they knew there would be few of those to contradict their claims. In other words, the supervisors did exactly what they were supposed to do: get rid of witnesses and give agents and officers time to get their stories together. Sector and Washington DC headquarters were sure of this because they had CIT present at those interviews. This is further backed up by the affidavit given by then CBP Internal Affairs Commissioner James Tomsheck.

The San Diego Sector Border Patrol Critical Incident Team left evidence behind at the scene, failed to collect all the evidence, failed to collect the victim’s clothing, gave the wrong video to the San Diego Homicide Team and then stalled for weeks until they finally claimed the video had been erased. CBP agents admitted to seizing witnesses’ phones and erasing videos and images of the beating and tasing.

Not a single agent or officer was ever held accountable. Former Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott was given a promotion.

Border Patrol:

- Rodney Scott - Deputy Chief, San Diego Sector.

- Chula Vista

- Ishmael Finn - Supervisor, Chula Vista. Denied medical attention and complaint.

- Gabriel Ducoing - Border Patrol Agent. Kicked Anastasio’s foot injuring it. Beat Anastasio.

- Philip Krasielwicz - Border Patrol Agent. Beat Anastasio. Is seen on video pulling Anastasio’s pants off, folding them and placing them in his unmarked Chevy Tahoe.

- Imperial Beach

- Edward C. Caliri - Supervisor. Claims he watched the incident.

- Scott Carlson - Border Patrol Agent. Helped carry Anastasio to marked car. Watched the beating. Guided paramedics in.

- Derrick Llewellyn - Border Patrol Agent. Helped take Anastasio to the ground. Handcuffed him. Carried Anastasio to car.

- CIIT

- Armando Gonzalez - Supervisor

- Victor Garcia - Senior Patrol Agent

- Joe Vaiasuso - Senior Patrol Agent

- Wendy Lee - Border Patrol Agent

- Mike Mannen - Border Patrol Agent

CBP:

- Ramon De Jesus - Supervisory CBPO. Spoke with crowd. Deleted evidence, but then pleads the 5th in deposition.

- Robert Petrin - Supervisory CBPO. Arrived as last tasing was finished. Said there were 15-20 officers on the scene.

- Jerry Vales - CBPO. Tased Anastasio 4 times while he was lying on the ground handcuffed while yelling “Quit resisting.”

- Allen Robert Boutwell - CBPO. Arrived after 1st tasing. After last tase, he helped cross Anastasio’s legs and bound them.

- Kurt R. Sauer - CBPO. Arrived when VALES started tasing. Helped hold Anastasio down after 4th tasing. Had his knee on Anastasio’s right arm and helped cross his legs.

- Shawn R. Alves - CBPO. Got rid of witnesses.

- Joseph Arcia - CBPO. Arrived when tasing started. Rolled Anastasio on his back to opened his airway.

- Benjamin Michael Brown - CBPO. Arrived when tasing started. States he only watched.

- Victoria Guzman - CBPO. Got rid of witnesses.

- Ernest Kalnas - CBPO. Arrived as agents were trying to re-cuff Anastasio. Helped DeJESUS delete evidence.

- Heather Ramos - CBPO. Got rid of witnesses.

- Paula Sable - CBPO. States she did nothing until he stopped breathing. Checked for pulse. Kept his airway open.

Paragon Security:

- Edgar Tamayo Asunsion - Got rid of witnesses.

- Michel Falcon - Got rid of witnesses.

- Stephen Robinson Guevara - Got rid of witnesses.

- Rhic Roberto Minas - Got rid of witnesses.

ICE:

- Harinzo Narainesingh - Hit Anastasio 3-4 times in the thigh with his baton. Took him to the ground. Cuffed the right hand. Carried him to the car.

- Andre T. Peligrino - Hit Anastasio several times in the thigh w/his baton. Held his legs down with his stomach to the ground as agents cuffed him. Carried his legs to the car.

- Maria Del Socorro Quintero Perez, Brianda Aracely Yanez-Quintero, Camelia Itzayana Yanez-Quintero, and J.Y., a minor vs. Dorian Diaz and Michael Fisher, Border Patrol Chief, et al., No. 13CV1417-WQH-BGS, U.S. District Court for Southern California, March 31, 2017, Pacer.com.

- San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151 Investigator’s Report, Detective D. Collins, I.D. 5303, report prepared on 6/17/10.

- San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151 Investigator’s Report, Sergeant David Dolon, I.D. 4332, report prepared on 6/3/10.

- Sewell, Ann, “Chilling new video of US border patrol beating immigrant to death,” Digital Journal, April 22, 2012, http://www.digitaljournal.com/print/article/323436.

- San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151 Investigator’s Report and Crime Scene Report, Detective Cindy Munoz, I.D. 4980, report prepared on 6/10/10.

- Ibid.

- San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151 Investigator’s Report, Addendum II, D. Collins, #5303, July 9, 2010.

- “Mexican man injured at clash on the border.” The Desert Sun, May 30, 2010. (p. 7)

- “Mexican man dies after clash with Border Patrol.” Santa Maria Times, June 2, 2010. (p. B4)

- Morosi, Richard. “Probe opens in death of migrant.” The Los Angeles Times, June 3, 2010. (p. 16)

- “Request for congressional investigations and oversight hearings on the unlawful operation of the U.S. Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams (BPCITs).” Southern Border Community Coalition, October 27, 2021. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/alliancesandiego/pages/3292/attachments/original/1635367319/SBCC_letter_to_Congress_Final_10.27.21.pdf?1635367319

- San Diego Homicide Case #10-027149, #10-027151, interviews.

- “Request for congressional investigations and oversight hearings on the unlawful operation of the U.S. Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams (BPCITs).” Southern Border Community Coalition, October 27, 2021. James Tomsheck affidavit. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/alliancesandiego/pages/3292/attachments/original/1635367319/SBCC_letter_to_Congress_Final_10.27.21.pdf?1635367319

- Serrano, Richard A. and Wilkinson, Tracy. “Mexico protests slaying at border.” The Los Angeles Times, June 10, 2010. (p. 3)