On why Latinos join ICE.

If you are confused as to how Latino Americans can become ICE, CBP or Border Patrol, come on in and have a seat.

This piece is for those of you questioning how Latinos and other people of color can become ICE, Border Patrol and CBP. My perspective comes from experience as a white Border Patrol Agent and from conversations I have had with agents, immigrants and Latino Americans. It should not be assumed that this encompasses everyone’s experiences. This is simply my experience in understanding what to many of us who are white, appears to be a bizarre phenomena.

Like most things in life, there are a variety of reasons.

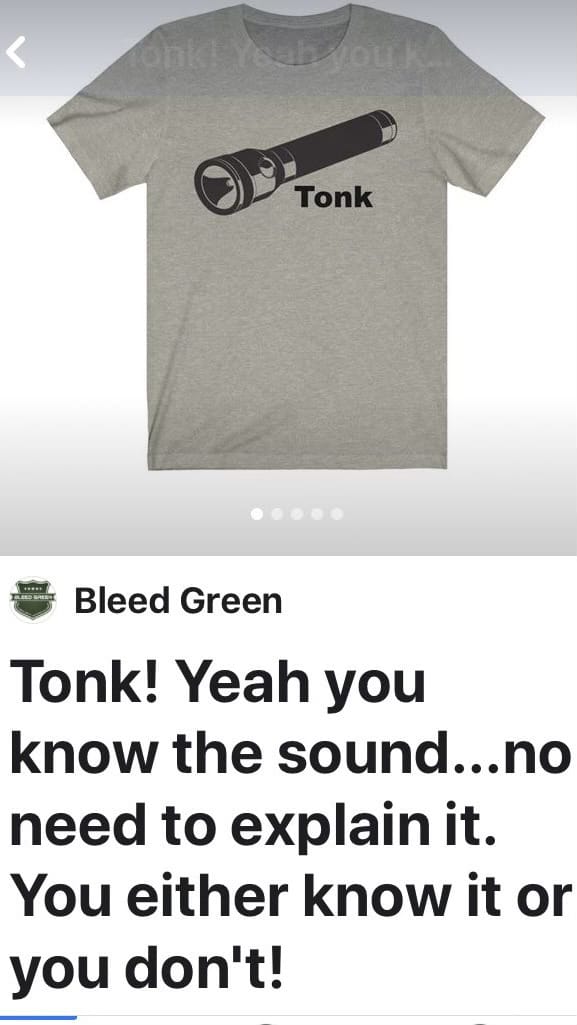

It confused the hell out of me when I was in the Border Patrol academy in 1995. My Spanish instructor explained that we California agents would not use the term “wetback” as he did because he worked the Rio Grande River in Texas. We would use the word “tonc” or “tonk.” As a twenty-four-year-old woman from Alabama who had not grown up around Latinos, save for the handful who were in name and skin color only, I knew his term was racist. I had never heard of the other word.

“How is it with being a Mexican-American and you are arresting Mexicans all day?”

Border Patrol agent Ortiz and my Latino classmates laughed at my question.

He said he hated La Migra when he was young because they would harass him as a kid growing up in El Paso. After high school, he decided to join because agents seemed to have it all. Just like agents today, he could join with just a high school diploma and no experience. It was his first job, and he was given a badge, a gun and immense power. He could drive big ass trucks, dirt bikes, ride horses and wear cowboy hats. The agents looked like him, came from the same area, had the same lack of opportunities, but they had the cool cars, nice apartments and hot ladies.

I can still picture his chubby cheeks blushing as he laughed when he said “hot ladies.”

He said that his parents had come here illegally. This made my eyes go wide, and he laughed again. He explained they were not criminals, but just good people looking for work. He was born in the US; something I’d heard some white people call an “anchor baby,” but I did not think it was wise to ask about this of Agent Ortiz.

When I was an agent, it was common for my coworkers to have parents who were undocumented. While stationed at Campo, California in the high desert mountains, a fellow agent became enraged at me after he admitted that his parents had come to the US illegally, but were given amnesty under President Reagan. He was angry because I had pointed out that his parents were in our vocabulary, “tonks.” He said I was racist, which caused me to laugh because he used the word all the time when talking about the undocumented or as we called them, “illegals”.

There is a cognitive dissonance some play to justify being an immigration agent. They can draw a line between their own experiences and the people they are arresting every day. They believe that when their parents crossed illegally, there was not a legal avenue. They believe that after Reagan’s amnesty, something that literally began the MAGA movement split in the Republican Party, there were plenty of legal avenues and that the people we were arresting every second of every day, were choosing to flaunt the law and cross illegally.

If you know anything about immigration law, you know that the amnesty was given in exchange for tougher crackdowns on who could apply to cross legally. And those restrictions that former President Clinton passed immediately following the amnesty, affected not just worker permits, but it criminalized immigrants who had entered legally and committed minor crimes. These were people who had perhaps a DUI and did their time or sentence. It could have occurred four months ago or forty years. It did not matter. People became “illegal” overnight. This then often forced those people to attempt crossing illegally.

It is notable that a US citizen can become a Border Patrol agent with prior DUIs, domestic violence and even sexual assault arrests and convictions.

What upset my coworker about me calling his parents “tonks” the most was not because he thought the word was racist. It was because he knew after years of working at the same station, ninety-nine percent of those we arrested had no prior criminal record of any kind. It was because he identified with the man I had been interviewing who had the same sing-song Mexican accent that comes from Sinaloa. It was because the connection to what he was doing was becoming thicker, and he did not like it.

“It’s different now!” He quickly swung back to his nonsensical claim.

I told him I knew what he was getting at; they were all criminals, and his parents were not script to which he nodded in agreement. But he was smarter than the others, and I took a chance.

“Jose, you know how most of the management is white men.” He interrupted me to point out that it was because there were so few women in the Border Patrol. “Yea, well that may be, but I am referring to the white part. We’re over fifty percent Latino, yet out of about forty managers, we got one Latino.”

He asked, even though his eyes said he knew what I getting at.

“You joined a racist organization, sweetie. Why do you think they teach us the word “tonk?” Why not use the other terms that already exist in the American culture for Latinos?” He looked up at me with his hands on his hips, silently asking me to shut up. Ninety-five percent of what we saw were his countrymen. I asked him how he would feel if we white agents were walking around calling migrants “spics” or “beaners.” He said that would be racist.

I explained how they developed that term so he would feel better about his work. “It’s so you do not see it as racist. You have to be white on the inside to get into management. Look at who gets selected!”

He walked away. I cannot say why he joined, but in knowing him I would guess that it was simply the best opportunity he had at the time. This is why Border Patrol is in classrooms all along the borders from kindergarten to college.

Then there are those who we referred to as being white on the inside. Many agents have Latino last names, may even appear Latino to us whites but do not speak anymore Spanish than we do. Others have military backgrounds who had much of their culture trained out of them. They identify more with the authority and power, the badge than they do with culture. Still others may come from countries that do not have a tradition of migrating to our southern border. Other Latino Border Patrol agents are Puerto Rican. They are by law US citizens, and do not identify themselves with the migrants they are apprehending.

The immigration enforcement agencies love it when people of color join. It affords them the opportunity to claim they are not racist, even though their entire history is based in Latino racism.

My Spanish instructor refused to tell me what “tonk” meant, saying we had to graduate the academy before learning the actual meaning. For the moment, he said it meant “Temporarily Out of Native Country” or “True Origin Not Known.” Throughout the entire training, I never saw any terms, immigration laws or policies describing the meaning of this word.

It was only after graduation and working at Campo that my Latino training agent said it is the sound our flashlights make when we hit a Mexican in the head.

Borderland Talk with Jenn Budd is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.