Border Patrol’s long history of illegally listening to your cell phones without warrants.

Under today’s authoritarian take-over of the US government with the immigration agencies being the tip of the spear of this violent insurrection, I recommend you all assume they can and are listening to your cell phones. That goes for political leaders as well; assume they are listening.

The Supreme Court of the United States decided in Egbert v. Boule that Border Patrol agents cannot be held liable for violating someone’s civil rights. While victims still have a right to complain to the agency about their treatment, this decision makes it near impossible to sue a Border Patrol agent for constitutional rights violations in order to obtain reparations.

I thought a great deal about constitutional rights when I served as a Border Patrol agent. Personally, I never believed that our checkpoints were legal. Stopping people on large interstates or small two lane highways without probable cause of a crime simply to determine someone’s citizenship is a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment’s right against unreasonable searches and seizures. At least that was what my law instructors at Auburn University taught me, but few agents had any education in the law other than what the agency drilled into their heads.

I also thought about the secret and little known unit in the Border Patrol called the Gremlin Unit and if it was violating constitutional rights as well. Like all agents back then, I had to wait until I became a Senior Patrol Agent to discover the truth.

From my memoir:

“I got a better idea,” he said holding up a black box.

“What’s that?”

“A scanner that can pick up cell phones. In Temecula, the smugglers contact one another by cell phones and not radios. We can listen and figure out their plans and stay a step or two ahead of them. We’ll be able to hear the lookouts telling them which route to take or if they are warning them about one of us up ahead.”

I knocked the cherry off my cigarette butt and flicked it out the window.

“What’s wrong? You look like you smelled something bad,” he said.

“It’s just that…it’s against the law. We need a warrant to be able to listen to private communications.”

“Oh, come on, Jenn. You don’t think we’re the only ones doing this, do you? Fuck, they listen to us! All the stations do this. Every sector does this. Agents ride around and listen to cell phone communications all the time. It’s just a tool to help us level the playing field. There are agents that do this all night, all across the border. If they get busted, we just say we were listening for cartel activity south of the border and no cell phones in the U.S.”

“What happens when you go to court and have to disclose that you were secretly listening to their communications? Doesn’t the judge throw the whole case out?”

“Not if you never mention that you did it. They don’t know what we don’t tell them. We just say the car was heavily loaded, proximity to the border, our experience as immigration law enforcement officers that this normally indicates that it is a tonc load and so on like we always do. Besides, constitutional rights protecting search and seizure are limited down here on the border,” he added.

I knew of less than a handful of agents who understood constitutional rights. The rules of searches and seizures, evidence, interrogations, arrests—all these things were lightly covered in the academy, but there was never any additional training after the academy in this area. The training that agents received after graduation and in the field contradicted the little legal training we had in the academy. Less than a handful of agents I worked with knew that the Constitution applied to all persons and not just citizens, that you could not legally just pull over any car with a Brown driver because you were on the border, that it was illegal for us to listen to cell phones without warrants.

When agents broke the law to get the arrest, they most often lied on the casework and stated that the driver had gotten away or absconded. Without the driver, there was nobody to prosecute and therefore nothing to evaluate and see that they were breaking the law. If the driver was a US citizen and they could not simply be returned to Mexico, agents would claim that the US Attorney’s Office refused to take the case even though they never even bothered to request a review of the case.

Even when prosecutors were interested in the case, they were often forced to decline it because agents had broken the law in order to make the arrest. Agents refused to take responsibility for their illegal actions and for not knowing the law. Instead, they blamed the U.S. Attorney’s Office, claiming they did not care about people entering our country illegally. For Border Patrol agents, it’s not about casework or jail sentences. It’s about pounds of dope, numbers of migrants and vehicles seized.This is still the case today.

My cases and a few others were rarely ever declined. If I didn’t have the level of suspicion needed to make the stop or it was not safe, I simply did not do it. It was not worth my reputation as a federal agent to violate the law or risk anyone’s life by asking someone their citizenship. It was a line that I was not willing to cross even though so many around me did.

“I don’t feel comfortable doing it. Honestly, I don’t even agree on having checkpoints. I’ve never agreed with the whole proximity to the border excuses to limit rights. Why should anyone have to be inspected for their citizenship just because they live close to the border? The Constitution doesn’t say the Fourth Amendment applies to all persons except those within so many miles of a land or sea border.”

“See, that right there’s the problem with hiring you college-educated dweebs.”

“Yeah, well, that’s how I am, I guess.”

“Oh, come on! They are fucking criminals! Listen!” He turned the scanner on and turned the dial until we could clearly hear someone speaking on a cell phone in Spanish.

“You hear that? There’s another load going. Scouts are everywhere. It’s just leveling the playing field. It’s what we have to do to catch the bad guys,” he said, trying to convince me.

“You can do whatever you want, but I don’t want any part of it. Besides, I cannot understand them. They are speaking too fast,” I said, thankful to have discovered an excuse.

“Oh yeah, maybe you should learn Spanish better,” he joked.

“Maybe you should learn English and write your own damn reports,” I said, laughing.

Gremlin Units were started by Border Patrol agents working the highways looking for loads of smuggled humans or narcotics once cell phones became prolific. Agents noticed that smugglers were using cell phones to communicate. They watched our checkpoint and the surrounding roads looking for the best times to try and smuggle loads through: when checkpoints were down or closed, when the side roads were not monitored for a variety of reasons, when the weather turned bad, etc. Lookouts then called the smugglers and told them when to run their loads.

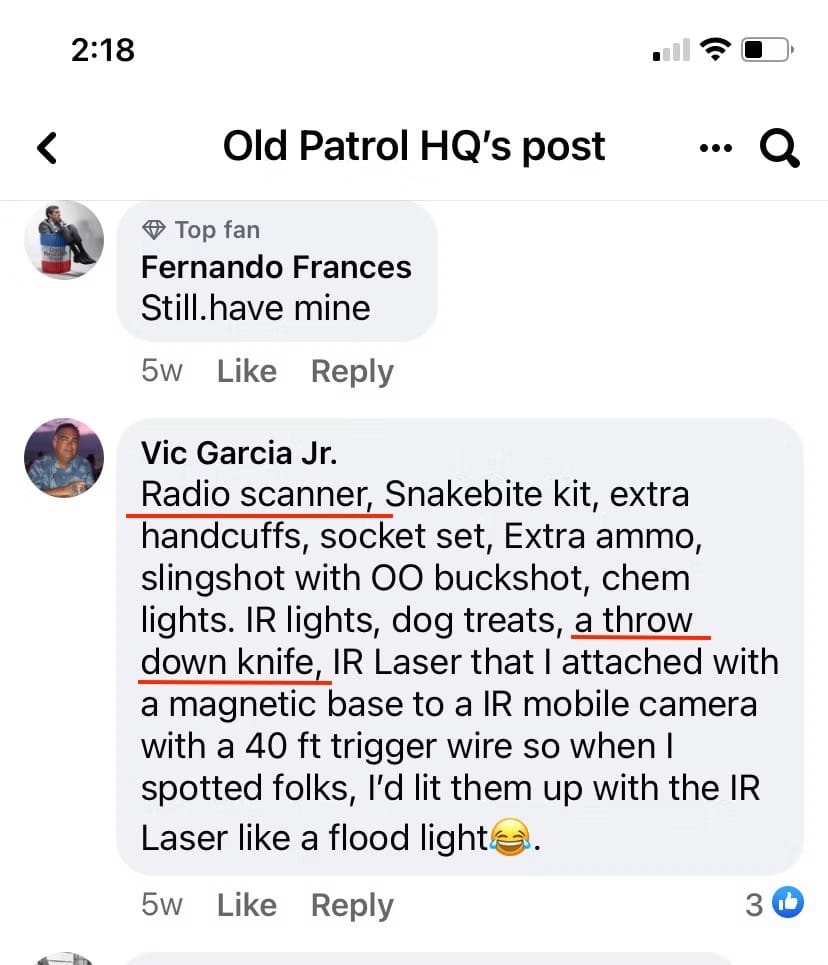

At some point in the 1980s, agents began buying radio scanners that picked up cell phone communications easily. They purchased these units for about $100 from places like Radio Shack and carried them in their “tricky bags” or duty bags. Agents then listened to the cell phone traffic. From the older analog phones, they could hear lookouts and smugglers talking. This is how Border Patrol agents could stop a car with only ten pounds of cocaine in it. The reasonable suspicion they used was made up: driver looked at the agent too long, driver refused to look at the agent, proximity to the border, blah blah blah. The truth was that they knew it had a small amount of drugs in it because they were listening to people’s cell phones.

This is completely illegal and violates the Fourth Amendment. Law enforcement is required to obtain warrants to listen to cell phones, but Border Patrol agents didn’t follow the law and didn’t care because they knew then and still know now that they are rarely ever held accountable. Most of the people they arrested were smuggling and most often pled guilty. Agents never admitted they were listening. They did not write in their reports that they were using scanners, and so the courts and defendants had no idea. On the off chance that someone ever discovered the scanners, agents routinely said that they only used it to listen to cartels in Mexico, and never listened to cars traveling within US borders.

That of course was a lie.

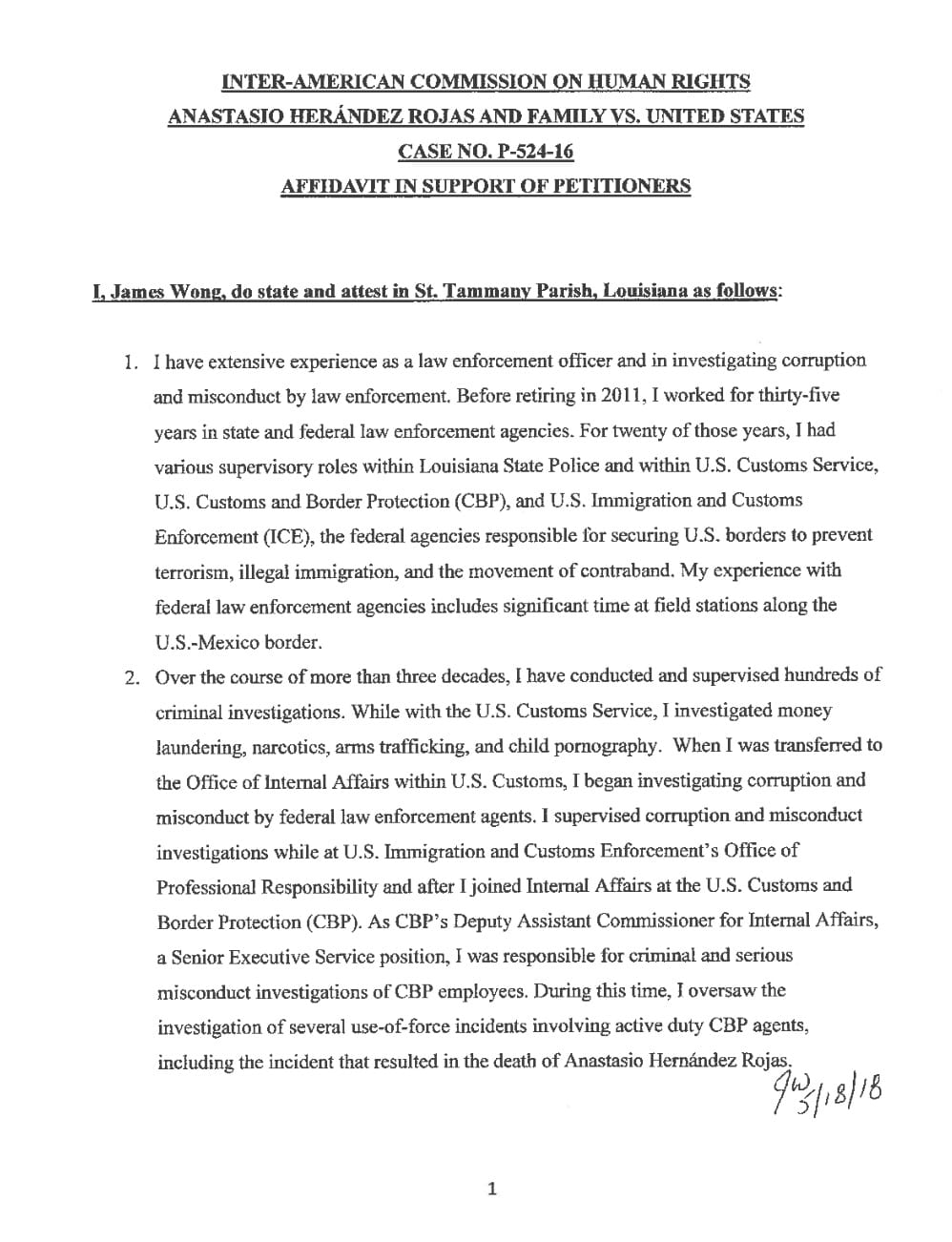

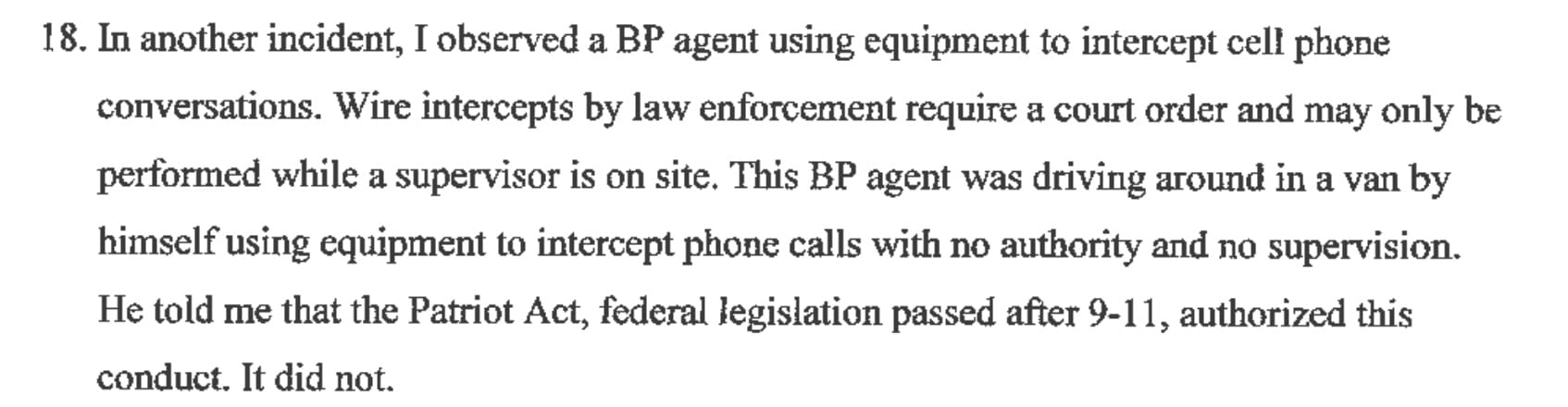

I’m not the only one who’s come forward about Border Patrol agents illegally listening to cell phones to conduct traffic stops for drugs and humans. This is what former CBP Deputy Commissioner of Internal Affairs James Wong had to say about it in a deposition taken in 2018:

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Anastasio Hernandez Rojas and Family vs. United States, Case No. P-524- 16. James Wong Affidavit in support of Petitioners.

Agents still use scanners today even though today’s cell phones are digital and more likely to be encrypted. There are still many smugglers out there using analog phones, and of course, there is the reality that agents are now using Stingray technology and other equipment that can unscramble the encryption.

Whenever I see an agent stop a car and there is a small amount of narcotics or only a few people being smuggled, I think to myself that they might be using a scanner or Stingray technology and listening because the reasonable suspicion cannot be that the car was “heavily laden.”

Under today’s authoritarian take-over of the US government with the immigration agencies being the tip of the spear of this violent insurrection, I recommend you all assume they can and are listening to your cell phones. That goes for political leaders as well; assume they are listening.